Posted by: Em | JUL-10-2020

The first and only time I had a chance to see Lee Lozano's work in exhibition, I blew it off. It was a momentary decision; just seeing a terse, alliterative name with no obvious gender implied, advertised alongside squared-off handwritten block capitals that reminded me of my father's handwriting made me assume it was probably some minor male 70s conceptualist or worse, some guy still riding the aesthetic with little development into the present. In hindsight, I now think Lozano would have found this hilarious.

I next encountered that squat, demanding handwriting in Max Haiven's Art After Money, Money After Art, which presents the text of several of Lozano's “strike” pieces that criticized the labour, social and capital flows of the New York art world, as well as a brief sketch of Lozano's career arc, which ended abruptly with withdrawing from forthcoming shows, withdrawing from making new work with a General Strike Piece, withdrawing from any women in the art world with a Decide to Boycott Women Piece, then any art world contacts, and finally any female contacts more broadly. My curiosity was piqued. At first, such moves seem self-destructive bordering on insanity, and many peers in the New York art scene of the time viewed it as an extension of a pattern of other volatile behaviour. But there was also something that struck me as startlingly compelling and effective about these actions.

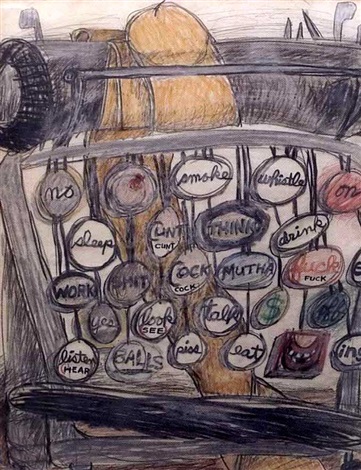

Lozano's commitment to art was whole-life; Lucy Lippard, one of my long-time curatorial role-models and allegedly the first victim of Lozano's determination to cut contact with women, described Lozano as one of the first artists to “[do] the life-as-art thing.” Lozano's last name was kept after a brief marriage, (which, despite its brevity, apparently involved the couple wearing difference-blurring matching outfits to art world events), the first name “Lee” an androgynous shortening of “Lenore,” though at other times Lozano simply preferred going by the letter E (my own first initial). Before the text-based conceptual “pieces,” Lozano's work consisted of vigorously rendered, but simultaneously funny and crass paintings and drawings of mouths, breasts, buttocks, genitalia alongside hardware and tools that appear to bend and squish ineffectively, and then meticulous, shimmering abstracts that explored energy wave patterns. Over even a truncated career, Lozano's work is omnivorous, provocative, and intellectually rigorous. From this position, how can dropping out not be a highly considered act?

At the time that I finally actually encountered Lozano's work, rather than my own impression of it based on a street sign, I was struggling to find stability in an art world that just seemed to take, becoming increasingly aware of the amount of free and extra labour melding your interests and passion with wage-seeking could skim away, cynical of networking, exhausted by my own fakey-fake job hunting personality, and becoming disillusioned with feminist oriented politics in my field that seemed to only aim as high as equal opportunities for gender conformity. I was alienated, I felt like an alien. I was also immersing myself in the literature of fellow aliens, the philosophy of Simone Weil, Chris Kraus' Aliens and Anorexia, Hamja Ahsan's refashioning in Shy Radicals of pathologized “depression” into historical “melancholia,” re-conceptualizing withdrawal from the world, its noise, its cruel systems, as productive and nourishing rather than self-effacing. Suddenly recollections from Lozano's peers– “Lee wanted to be a bad boy very much, then she got irritated because she always a girl in the end” –seemed to come from a place of cruelty or derision rather than concern.

To see Lozano's work as simply self-destructive, or in the case of the Boycott Women piece in particular, simply misogynistic, to describe these works as merely “behaviours” emerging from mental illness or drug use is to attempt to discredit the aspirations encapsulated in withdrawal, to explicitly frame non-participation, the refusal of the horizons defined by the art world feminism and labour movements Lozano often clashed with, as “crazy.” It's a reigning in of possibilities looking beyond, and also a re-disciplining of one's own reasonable, even entrepreneurial participation. There's also something particularly raw about the Boycott Women piece especially, initially formulated as a way for Lozano to “better communicate with” women, ending up a sort of formalization of the visceral wincing away from platitudes about "the feminine" or "sisterhood" when you're not a enthusiastic gender-fit that gets turned on various gender-ambivalents as "internalized misogyny" for others to tut-tut at.

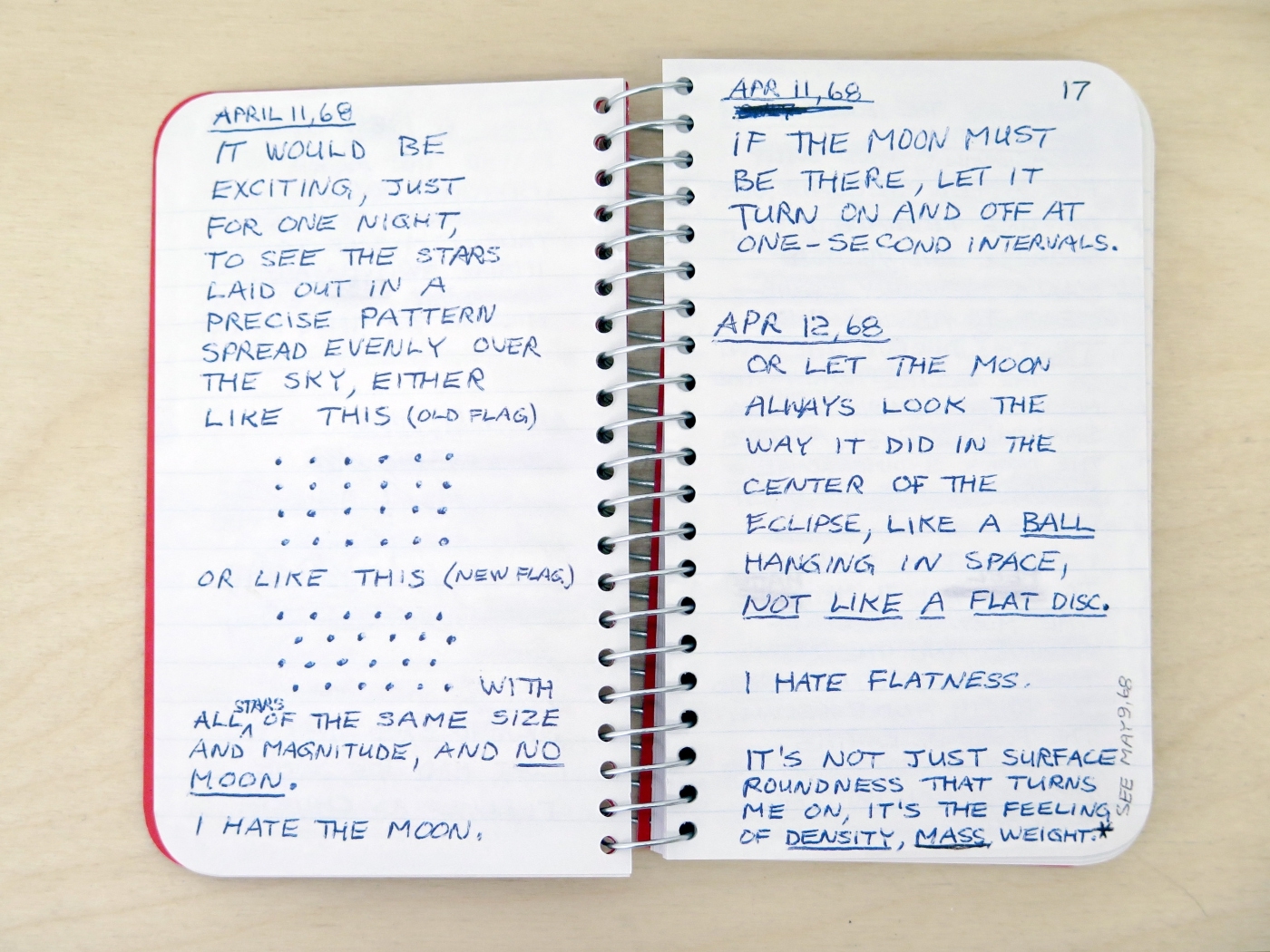

Lozano's day to day notebooks, “Private Books” recording phone calls, to-do lists, frustrations, transient thoughts and drafts of the practice-based “pieces,” are also made available as replicas in the spirit of art-as-life. There's pages of fretting over changing hair styles or planning new, masculine wardrobe choices like button-ups and leather jackets, re-examining awkward professional interactions with peers and curators at obligatory art openings and dinner parties, and ideas for practically unrealisable artworks, including rearranging the stars. There's also phrases that jump out, “I seem to look at my life the way a junkie looks at his arm,” “This life has a toothpaste dribble stuck on it,” as both the regard of one's life itself as a sort of art material, and, at the same time, indicative of despair at the gap between what can be felt, thought, or aspired to, and the imposed “reality” of one's situation.

Far from defeatist, Lee Lozano's work was aspiration at the highest level, to the point where it can only feel counter-intuitive, antagonistic, like not playing along. Naming the terms of non-participation in the art world “strikes” and “boycotts” alongside other conceptual works that played with how the supposedly autonomous sphere of art is always entangled in social conventions around money and labour, Lozano brings into the imagination, if not into being, a world where art is vital enough to life and society that a strike action doesn't immediately seem like a self-defeating disavowal of something that is done only on a personal level out of love, passion, nature, privilege or compulsion. Shortly before the Wages for Housework movement also examined gender along the lines of discipline and labor rather than nature, the Decide to Boycott Women piece similarly presents a further horizon than a reparative women's canon, equal representation, or the promotion of “feminine” art, where the strain and expectations of gender difference can be excised from one's personal and professional life like quitting a bad job. Maybe these options can't exist now, and that is why Lozano's actions necessarily led to the abandonment of an art career. But there's no reason why they couldn't exist, maybe tomorrow.