Posted by: Em | APR-22-2025

NB: Hey! Long time no post, here anyways. I have mostly passed from the realm of theory into the realm of practice, for reasons that will be elaborated on in the talk below. It's an edited transcript of a talk I gave at the Glasgow Games Soapbox (which you can watch video of here), as well as Everest Pipkin's course on Browser Games. The talk touches on a lot of things I've articulated in previous essays on this site, so is not totally new ground, but maybe slightly new angles to think from.

I find myself writing significantly less essays on games and tech stuff because I am basically... doing what my values argue in favor of most of the time I'm not doing my boring dayjob now. In a way, I felt kind of unqualified by now to write a talk, but it went over well. The majority of my free time is spent on Domino Club, my other, more freeform/personal blog, and fiction writing. This site will stick around as a portfolio and archive, but it's not my primary space for writing any more, because the writing I do is very, delightfully, different now. Anyways, enjoy the talk!!

Here are some things I find kind of annoying when people say them about non-commercial games or other projects. You might laugh if someone has said them about your own work, or if you’ve said them yourself maybe think about the ideological assumptions built into them:

“That’s a good start. You can use those skills on a real project.”

“It’s free and it only takes 10 minutes to play!”

“Obviously your work is valuable, but I’m talking about people who want to make a career doing this.”

These sorts of statements reinforce noncommercial and freely available online work as marginal to the “real” commercial products of the gaming industry… a sort of field of potential talent, tools, new ideas and the care work of making space for marginalized narratives and forms of representation that is free to swoop in on, pick and choose from, and use for their own purposes.

But video games didn’t start as an industry, they started as timetheft by programmers in university, government and military labs who were meant to be doing something else. While its entanglements with the military and technological control society which are pillars of capitalism are also strands of videogaming as a field that must be reckoned with, I would say it is shaped just as much by these illicit beginnings, as well as software crackers, personal computer users, and those who maintain their own strange gardens online – as its currently hypercompetitive commercial formation.

I started writing about games in 2013/14 or so for Arcade Review, with a focus on the RPGMaker scene of the time, and how it was influenced by older horror games which used the engine against the grain to make games that were often distributed free online.

After I finished college, I interned at SAAM, which has a very interesting media arts collection and also put on a major exhibition about videogames, which I found kind of safe and underwhelming in comparison. It didn’t excite me like the stuff I was digging up online was. I got into a grad program to further research games and interactive works in art exhibitions from an art historical perspective– ie, how are they contextualized? What does the gallery space and how they’re set up convey about them?

I got to do some interesting research and also put together some exhibitions and workshops on the topic. I was fascinated by the possibilities open source and interoperable engines like Bitsy presented and was also strongly inspired by zines and old web cultures that prioritized accessible distribution and preservation of niche topics in ways mainstream culture did not really officially allow…

So that was really great, but I also graduated almost directly into the COVID-19 pandemic. Suddenly in-person events and hands-on exhibitions were obviously in low demand. I had already been struggling with the feeling that the work I valued would always be considered secondary to the packaged commercial products that were seen both as more legible to mainstream game histories and the concept of the art object that dominated academic game studies and their reception in the art world.

I was flirting with burnout, and trying to pivot to doing online event organization on a freelance basis didn’t help. Because I was also immigrating to live with my partner, it turned out to be a much better option to take a mostly-unrelated day job (adapting print textbook materials to digital and online formats for an education company) that would support my case of consistent UK residency, and that’s pretty much what I’ve been up to since mid 2021…

On the official employment front. Since then, though, I’ve continued making free interactive fiction web games, mostly using niche, open source engines and through the collective Domino Club (whose members also develop many of these engines). I started a small zine distro which distributes writing about these DIY art practices as well as just random stuff people send in to me, and we’ve had tables at zine fairs in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dundee and Carlisle, and even exist in a few consignment shops… I’ve even written one novel which I’ve published through a local small press and am working on another.

I subscribe to the theory of personal art practice as a type of excretion; it’s going to come out anyways. I have found these practices and the other game collectives, individual creators, zinesters and writers I meet in the course of my own practice to be extremely nourishing. People who are doing these things, even as naturally as it may come to them initially, are also working against enormous odds. They are working against the odds that a process like “enclosure” has happened to basically every new media that has emerged from people’s everyday culturally reproductive activities.

By “like enclosure” I mean the historical process generally considered to precede capitalism and the establishment of the wage labor relation in the UK – areas where subsistence crops could be grown, houses could be set up, and resources gathered by the people who lived there were changed from being commons to privatized for the use of a single owner– the economy then shifted to the inhabitants having to work for that owner or pay rents to use the land to survive.

This is a simplified summary, but in general this sort of process repeats any time freely given labor, done for the necessity or joy of it, and common resources are spotted by capital. Shut down free development and sharing with proprietary platforms and IP law, start charging the people who are already there rents to go about the same activities, professionalize, squeeze out amateurs, and elevate commercial production as the legitimate form of production in a particular field.

Despite how well resourced and legally reinforced these practices are, almost to the point that it seems hard to imagine, for example, a world where you don’t have to continuously rent your own shelter from someone else, people still manage to do work that escapes this process, which I think is important to foster via historical and critical attention.

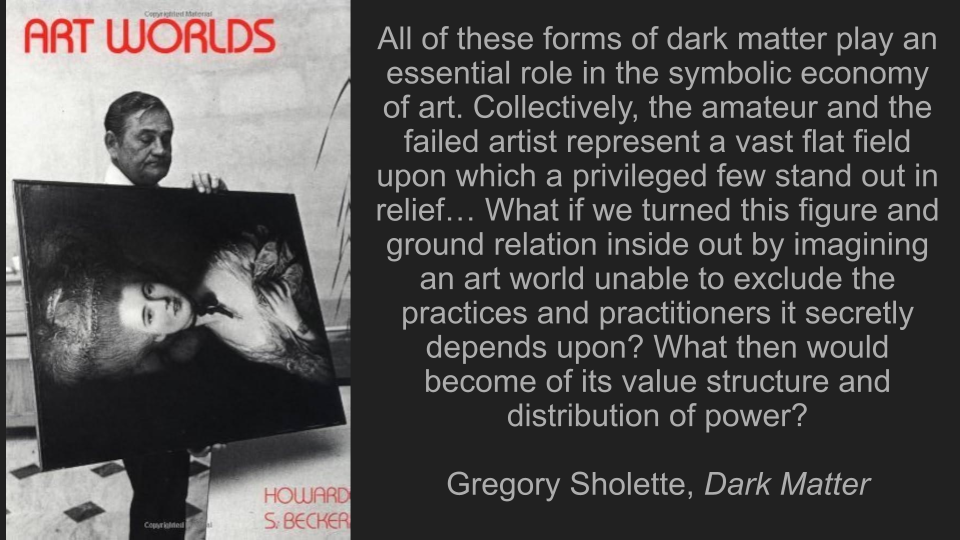

The sociologist HS Becker wrote the study Art Worlds out of his interest in all of the social and physical elements that went into, perhaps, one work of art reaching the pinnacle of ‘masterpiece’. It needs to exist in a tradition of others who did the same, and surrounding critical infrastructure to draw attention to masterworks. It requires a variety of professional artists and passionate amateurs invested in the medium, and participating in the contextualizing and critical work around it. It needs the staff at museums and galleries, it even needs the materials and workers which make the standardized art supplies that are made available to the public. Studying contemporary art production, Gregory Sholette identifies many of these practices as “dark matter” of the arts as a field; kept invisible by, and invisible to “official” culture, yet essential to the form it takes and processes it involves.

Art Critic Hito Steyerl even observes that the prestige of big budget artworks, whether they be films, AAA games, or the rarified cohort of artists represented by blue chip art galleries, relies on fostering exclusion, hierarchy, and envy; "the more unpaid interns, the more expensive the art." Not everyone can be a modest or sustainable success for this system to reproduce itself, as is evident from the ongoing layoffs and shutdowns of studios that completed commercially successful projects… they just weren’t successful “enough.” In fact, the majority’s labor in the games industry and the arts more broadly is appropriated for free and they’re lucky if they see a few dollars thrown into their paypal. The pyramid which directs all resources and attention up towards a tiny tip starts to look like a pyramid scheme.

So, this is my pep talk for instead upending the pyramid, and attending to these marginal practices not as something that needs to beg for its presence alongside the commercial history of gaming but as preceding and appropriated by “mainstream industry:”

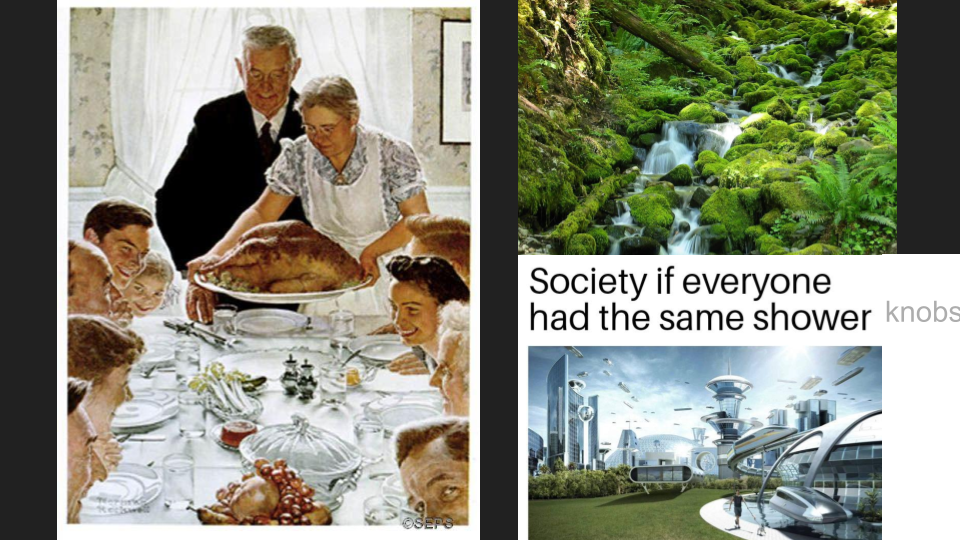

When you think of the concept of abundance, what do you think of? Maybe the image that comes to mind is a Norman Rockwell-esque holiday dinner table, a lush natural landscape, or the futuristic cityscapes from those “society if” memes. These abstract depictions of abundance are also orderly, it can’t just be anything that’s purely multitudinous.

In fact, things that are too abundant become a bit intimidating. The philosopher Georges Bataille called the immense output of solar energy that hits the earth beyond what existing organisms need to fulfill their biological functions “the accursed share,” which he theorized as an excess that underlies all life and must be wasted. It could be wasted on beautiful things, like artistic expression and non procreative sexuality, or terrible things, like war and violence. This excess can reinforce the existing order, as pressure release valve or monuments to its glory, or be used to disrupt it.

From that perspective, an uneasy element to abundance emerges, which explains our attempts to rationalize it. Think of the cringe with which you regard corny poetry or goofy fanart that seemed to flow out of you uncontrolled as a kid… the derision aimed at the cumulative monuments to this excess and abundance, like Deviantart or the sonic fandom. But isn’t this also abundance?

The firehose of passionate and strange work, mostly naive or indifferent to “good” game design practice represented by the “new games” tab on a site like itch.io (only one site representing one medium out of all human creativity has devoted itself to) can be overwhelming; how do you even know where to start? And the internet has made us more aware of this abundance, so knowing only an infinitesimal portion of it can be comprehended or archived for posterity can inspire a kind of dread.

Past a certain point, we start feeling like cultural abundance has to be culled to a representative sample and archived as a “style” or Movement, disciplined into proper artistic techniques and subjects, made into something that’s optimized within arcane algorithms for hits or likes, and, most importantly, commercial success. To keep indulging that capability without these things can seem from the outside like a quixotic delusion.

But is discomfort with abundance locking us into the way things are? Politically, austerity, tough choices, and privatizing public services so they have to run themselves like businesses has become ubiquitous. In response to anxiety over climate change and habitat depletion, we’re told to individually mind how much video streaming we do instead of pointing to capitalist structures enclosing and destroying natural abundance. Even our dwindling free time should be used for some progress, self-improvement, bits of flashy content or a monetizable hobby, or a sense of disappointment and inadequacy starts to seep in…

Thinking of my creativity as abundant rather than something that must compete and survive in a world of manufactured scarcity is one of the main things that has kept me going, through dry spells, setbacks, frustration, and life getting in the way. I make zines, I write, I do interactive fiction games, I doodle poorly, I cook new dishes, I joke around with friends, and all these things are a record of my mindset and experiences over time, stuff I end up doing even if I don’t have any objective reason to.

Like solar energy, it comes out when or how it does, but more importantly, even when I’m not actively writing, or coding, or whatever, there’s still the circuits where these excessive things circulate, websites, zine fairs, and other communities of practice where I find support and feedback that always means more to me than any engagement metrics.

Arts funding, prestigious industry roles, and other high-profile opportunities framed as chances to “make it,” either financially or in terms of acclaim, demand more intensive application processes and higher requirements even as their number and stability dwindles, out of the idea that making stuff is only worthwhile when it’s a rare and unique skill. The scarcer the opportunity is, the more tests are needed to ensure it goes to the single most right or worthy idea. But this is a very timid and limited view of what’s out there, and what’s possible.

Attending to the abundance that can be uncomfortable at first shifts the focus on stars and success, and resultant pressure, and instead considers the contexts work is casually made, distributed and discussed in, which has always been the foundation of singular “great” works anyways. It also helps ensure that when this generative excess disrupts the existing order, it’s in a positive and expansive way, bringing about worlds and possibilities that we may not even be able to see from our current vantage point.

Given the pervasive issues and instability of the games industry in particular and capitalism in general, exploring these possibilities is vital to envision a path where, as Marina Kittaka says, we all have the autonomy to divest from the games industry, and to live life for our values, not the work-clock.

At this point in the talk, I usually went over some examples of web-based, open source, interoperable game engines and tools that I've used, and responded to questions from the audience about particular ones they're interested in. The list includes:

And don't limit yourself to just game tools! Google docs can be a great way to put words and images together, and lay out PDFs for zines, journalgames, and more. Don’t underestimate just making HTML pages by hand too! Dating Ariane was one of the first internet projects that inspired me, and I made my own museum minisite. Games from the list that can be exported as an HTML document can often be embedded directly in blog posts, other itch pages, and more!

While self-maintained websites can go down and browser features changing can break them, they can often be more hardy and long-lived in preservation terms than typical commercial games. There's a lot of aspects that contribute to this-- because they are small file sizes, open source, and often very human-readable code (for the majority of my own projects I wrote or made modifications to directly into SublimeText), they are portable, easy to mod or debug, and of course aren’t locked behind corporate IP law or proprietary software and filetypes… for the most part. (RPGMaker is locked down to some extent but also has a lively lockpicking community.)

Open and easily readable code also means you can do fascinating stuff with nesting and combining works that can be its own sort of preservation, like World of Bitsy. I think this really speaks to the dream of the early internet and digital culture where sharing, editing and combining were fundamental, and shows how these games and the communities around them can be levers for critiquing and seeing the commercialized manifestations of gaming and the internet that have emerged since then as not necessary or inevitable.

If you want to explore even more weird webgames and communities of practice around them, there's the DOMINO CLUB RANDOMIZER, other game collectives like Lithobreakers and Gardens of Vextro, and, of course, Glorious Trainwrecks.

Thank you for your attention (in person!) or time reading this (online!). It really means a lot to me.