Posted by: Em | JUL-26-2018

This is a a transcript of the talk I gave at DiGRA 2018, along with slides including citations. It’s different from what I usually post here, but a good snapshot of what my current research is about. This is a condensed version of themes that I explore in the middle chapters and conclusion of my dissertation.

Hi, I’m Em Reed and I’m currently writing my dissertation on videogames exhibited in art spaces at Abertay University. This talk presents several ways that videogames have been displayed, specifically in cultural institutions that still center the idea of offering an encounter with a privileged, authentic object. Video games are entering art museums and galleries as well as design museums, through temporary exhibition and sometimes collection.Museums and art institutions are primarily oriented around the display and collection of objects that are specific, stable, and catalog-able within the existing institutional structures. Because new media works, including videogames, can be inherently unstable, relying on a mesh of things like software, hardware, updates, plugins, peripherals, internet connections and more to work as intended, the questions of how to preserve these works and how to display them after inevitable change over time remain open.

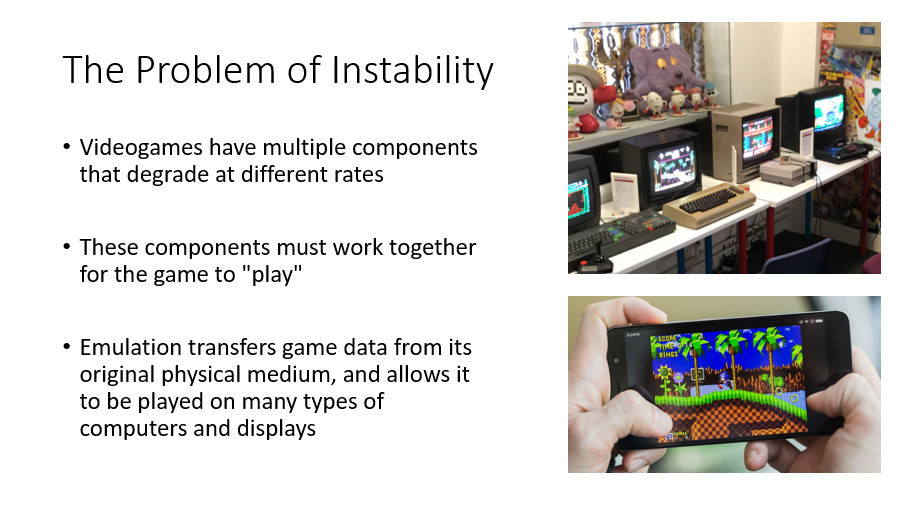

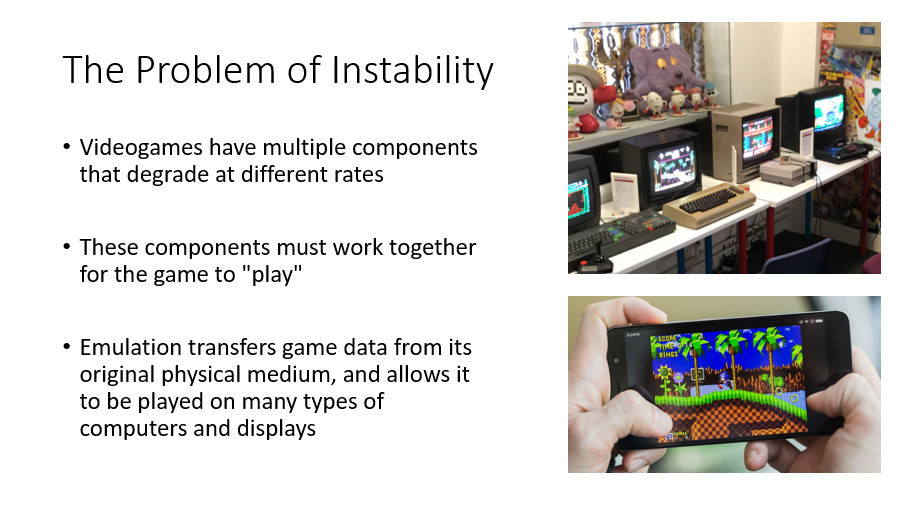

James Newman describes the videogame as an unstable object. Videogames cannot be reduced to a single preservable object in the way that artworks and archival materials can. In addition to the degradation of consumer-grade plastics that make up the cartridges, consoles and controllers, the formats holding game data, such as circuit boards, magnetic tape, or discs also have limited lifespans, and a videogame typically requires these things working together to be playable.

Institutions have primarily approached this problem via emulation, in cases where the original hardware is unreliable or no longer functional. This allows the videogame to run on many different machines and in many different contexts.

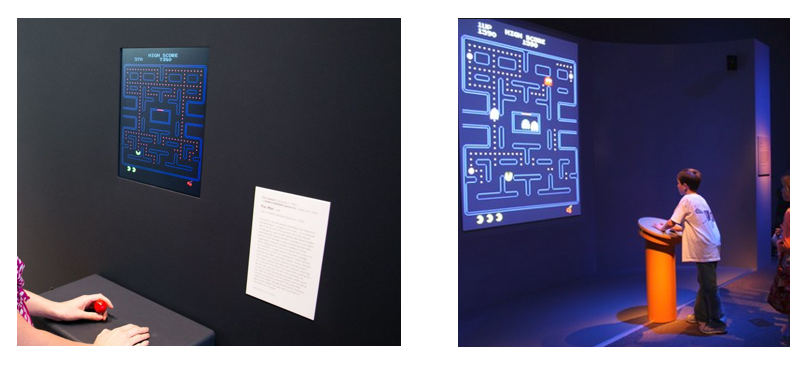

For example, this is why we’re able to see the arcade game version of Pac Man projected large scale at the Smithsonian American Art museum, and presented as a flatscreen kiosk built into the wall in The Museum of Modern Art.

But emulation is still a legally gray practice, and museums are relying on the archival work and programming of fans. These enthusiast game preservationists have created impressive online libraries of videogames and tools to access them. Yet, these games remain vulnerable to legal takedowns, web hosting fees remaining paid, and enthusiasts maintaining the free time and motivation to continue working on the projects.

Beyond these things that could potentially go wrong, emulation effects how videogames are displayed and how they are interpreted as objects by the museum or gallery visitor. Raiford Guins expresses concern that emulation, being able to present games anywhere, on any type of screen or controller, erases the historic interfaces and whole-body interactions that contextualized videogames originally.

While organizing the exhibition Hot Circuits, a collection of 70s and 80s arcade cabinets at the Museum of the Moving Image in 1989, curator Rochelle Slovin was concerned by the “content focus” of both game criticism and game consumption at the time. She considers the “jaded arcade owner” who would swap games in and out of their original cabinets and repaint the cabinets themselves, and the “screen focus” of the academics and psychologists studying games at the time to demonstrate the same disregard for the games’ context.

On the other hand, Melanie Swalwell argues that the role of exhibitions and collections of videogames should not necessarily be the most elaborate reconstruction of an imagined “original” experience. Even within experiences contemporaneous to the game’s release (such as a game being manufactured for an arcade cabinet,) there is an abundance of variety and subjectivity. Swalwell also cites the example of early text adventure titles that require a certain player vocabulary unfamiliar to modern computer users. These issues demonstrate presenting the game with an authentic interface alone may not be enough to effectively “preserve” why videogames are important or relevant.

Emulated videogames are often displayed in standing kiosks which mirror the one-size-fits all displays offered at trade show exhibition contexts, and have become a common display approach for videogames in art exhibitions. This method of display, like the “content focus” Slovin references, places the object of the videogame at the point of one-to-one interaction between a player and what happens onscreen. Not only does this shape the installation style of the exhibition, which in turn determines the experience of the visitors. It also shapes collecting practices.

The MoMA does also collect original hardware and software as a part of their design collection. However, curator Paola Antonelli emphasizes that “In order to be able to preserve the games, we should always try to acquire the source code.” Even if the games are not running interactively within the gallery, such as in the case of complex, longer format titles like Dwarf Fortress and Sim City 2000 that are presented in the form of video clips, the collection policy is oriented towards the code. This code being “playable” in the form of one-to-one interaction with a user, becomes the object that is both displayed and preserved. Rather than adapting institutional processes to the instability of the videogame object, this approach isolates an element of the videogame that makes it a “thing,” in the way that a sculpture or painting is also an object.

So, despite these challenges, do people play videogames in museums? Is this the authentic experience the institutions offer? Or, beyond that, with the emergence of live streaming, idle games, and live streaming idle games, do typical models of interaction and “playing” a game still make sense?

Multiple perspectives in Game Studies complicate the idea of the preservation of interaction equaling preservation of the game object. James Newman mentions the multiple ways fan culture, modding, speedrunning and walkthroughs change and add meaning to videogames. His work also complicates interaction or play-centric interpretations of games by drawing attention to the variety of levels of control in different moments of play, and the variety of “controlling” and “non-controlling” or “primary” and “secondary” roles for players. Austin Walker as well as Stephanie Boluk and Patrick LeMieux have written about how live streaming, competitive, and spectated play also change the nature of games. Most recently, Sonia Fizek has examined idle and self-playing videogames through the lens of interpassivity, a counterpoint to interactivity that recognizes pleasure in outsourcing supposedly enjoyable tasks, like playing, to bots or the automated processes built into the videogame itself.

New Media Curator Beryl Graham also problematizes a focus on interactivity by stating that most “interactive” technologies, as presented in art exhibitions and museums, are merely reactive. She separates the definition of interactive, where each participant acts upon the other, from the typical uses of immediate command and response relationship between user and code. It is important to consider what we mean by interaction when evaluating whether it is truly necessary to conveying understanding of a videogame. Most videogames, while having billions of possible combinations of button presses or moves that can complete the game, still only react to a player in a pre-programmed way. Arguably multiplayer games or games which allow for user generated content could be seen as facilitating actual interaction, by Graham’s definition, but these features are often removed or limited in exhibition contexts.

Discussing the potential for “zero-player” games, Jesper Juul and Staffan Bjork note that almost all broader and non-technological definitions of games, many of which are also used to discuss videogames, contain reference to the player as a vital element. The presence of the player and their direct interaction is seen as inherent to games and by extension videogames, and what contrasts them to “passive” or “static” media. They note these player-centric definitions of games, have a weakness in that they do not take into account what the “player” of the game actually does, or in the case of what I’m discussing, what they often do not do.

Art Historian Claire Bishop is also critical of the idea of direct participation in art being framed in exclusively authentic, utopian terms. Drawing on reality TV and social media as examples, she argues participation alone is not necessarily empowering or enriching. Further, a binary contrasting spectatorship as passive and participation as active inherently maintains inequality and separation between these roles, according to Bishop: “either a disparagement of the spectator because he does nothing… or the converse claim that those who act are inferior to those who are able to look, contemplate ideas, and have a critical distance on the world”

I think these theoretical perspectives map well to the practical reasons it is also important to consider non-players in gaming exhibitions. Rather than elevating one state over the other it is important to explore what each offers, and if there are examples between or combining the two. This is what I would like to discuss for the rest of the presentation. The exhibition approaches I cite are not an example of the ex-game or artifact, like the “brown box” Magnavox Odyssey prototype kept in storage at the Museum of American History; objects that are considered too delicate, unique, or unstable to be displayed interactively, and must imply their function and historical context under glass. Nor are these approaches completely “playable” in the sense of the term meaning the one-to-one interaction that is usually considered gameplay.

These following approaches present videogames as performed, as spectated, and as spaces of exploration in ways that do not foreground the singular interactive experience, and in the process they discover ways of working around the shortcomings of both artifact and interaction-centered exhibition types.

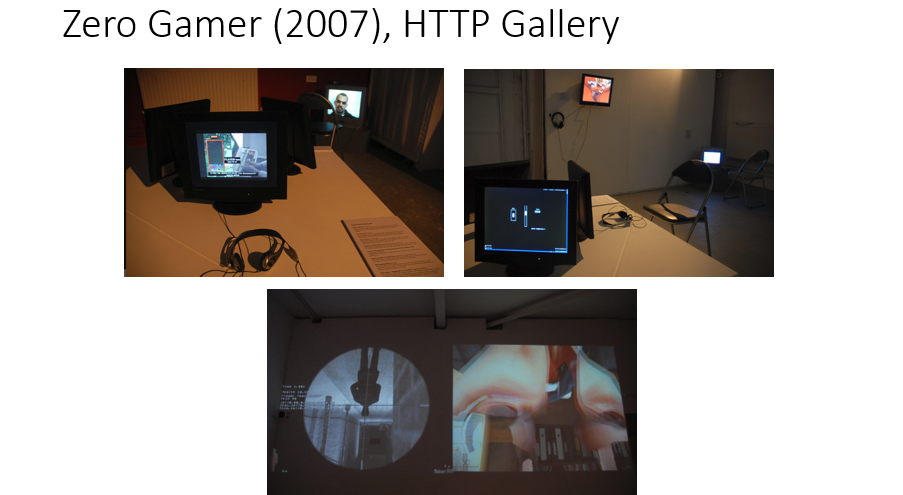

An early example of this is the exhibition Zero Gamer, organized by Furtherfield and HTTP Gallery in 2007. Zero Gamer was a non-interactive videogame exhibition that presented machinima, self-playing games, and gameplay videos as the primary object, and not just to provide context for the interactive videogames. The exhibition was presented as a counterpoint to contemporaneous discussions surrounding videogames that focused on interactivity. Most of the work was from artists in New Media or Game Art movements, but there were also works by independent game designers, and videos of speedruns or mods of mainstream games.

The essay accompanying the exhibition describes “pauses, breaks and interruptions” as “the backbone of gameplay experience,” and that meaningfully interrupting the playing process facilitates “a platform for reflection,” removing players from the immersion or flow state of interaction. Additionally, the exhibition essay notes this “allows the audience to engage with crucial issues arising from the hugely complex field of games and gaming … without actually playing.” The introduction offers an alternative way to view the gameplay videos and self-playing games as more than just “non-interactive,” instead stating “the works in this exhibition don’t remove all action from interaction, but they do shift the sites, times and agents of action.”

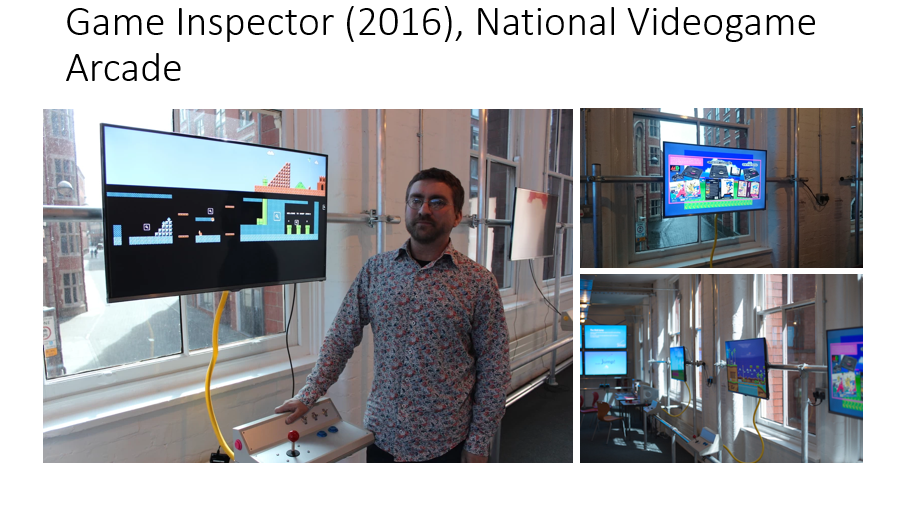

A different approach is demonstrated by the Game Inspector system developed for the National Videogame Arcade in Nottingham, UK. These displays allow visitors to see an entire level or area of a videogame on a large screen. Visitors can also zoom in to find historical details, facts about the game, or archived videos of gameplay at certain points in the level. Piloted with classic games like Sonic the Hedgehog and Super Mario Brothers, Game Inspector offers a possibility for elements like glitches, secrets, and instances of particularly skilful play to be accessed and understood in the larger context of the game by visitors. These are elements that they may be unlikely to understand or access playing the videogame themselves.

The system can serve as a supplement to the many interactive games the NVA has on display, or a standalone work presenting these games in a modified way. While these displays are interactive, they do not involve “playing” the game itself and therefore have an ambiguous role in an institution that presents playable games as well as videogames and consoles as static memorabilia or illustrative items. I think this is a productive ambiguity that presents videogames as highly multifaceted, beyond an idealized, singular “player experience.” This ambiguity could backfire however, if the system is simply seen as an “interpretive aid.” New Media artists’ works that have taken the form of things like websites or audio tours, common interpretive aids, have frequently been removed by the institutions presenting them and subsequently lost. To ensure the longevity of the archival insights offered by Game Inspector, it is important that it’s not considered only an interpretive tool.

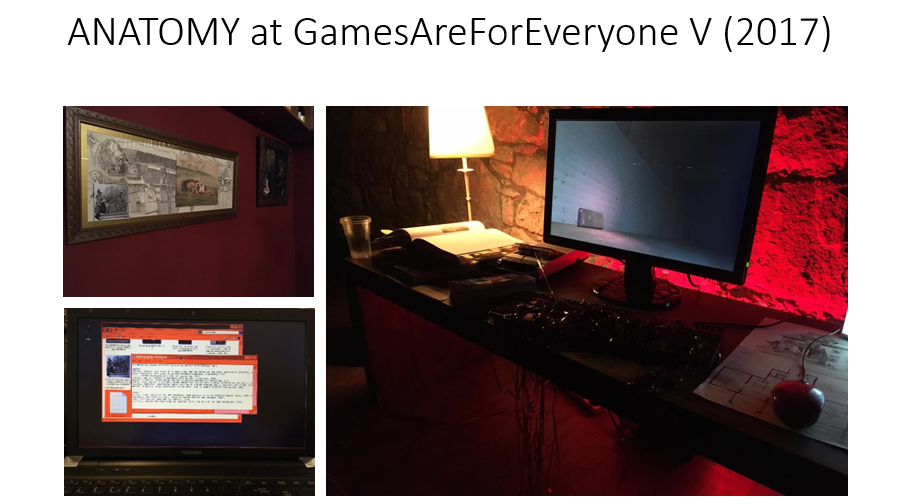

Finally, my own work curating a custom installation of Kittyhorrorshow’s ANATOMY for Games Are For Everyone V offered a whole-room environment to support a single-player game. During the event, I was able to observe both spectatorship behaviors as well as forms of indirect interaction, such as offering advice, sharing controls, and drawing hints from the environment, which allowed many people to participate at once beyond the person at the controls. For this installation, I specifically selected a Horror game, because the genre is especially popular among lets players, and the comments on these videos demonstrate a variety of participatory behaviors, such as offering the Let’s Player advice, identifying with their reactions to scary moments, and discussing or interpreting the game’s environment or plot for clues.

To facilitate this experience in an exhibition context, I first selected a mechanically accessible game from the Horror genre. ANATOMY is focused primarily on narrative and atmosphere, and has no combat, fail states, or areas where the player must react quickly. I extended the visual aesthetic of the game into the player’s space through lighting, room décor, and making the control interface look similarly damaged and degraded to the degrading visuals in the game. I also treated the computer the game was played on as a space, making the desktop theme (which would be revealed in between story beats where the game would suddenly close itself) reflect the retro and glitchy graphics of the game. Finally, I accompanied the installation with a selection of images and texts, both inside the display computer and in the room itself. These documents added to the atmosphere of the installation and expanded upon the game’s narrative themes. By taking cues from the social and spectated ways horror games are now played, I was able to make an installation that encouraged several people to engage with a longer format single-player game at once, a problem of duration that arises frequently in the display of videogames.

So, based on my research and curatorial practice, I believe it is important for exhibitions to engage with the experiences that don’t straightforwardly fit into the paradigm of one-to-one interaction, or, alternately, static artifact. In fact, it is important to acknowledge these modes of attention and reception within exhibitions because people are already doing it. As early as 1996, during the exhibition Serious Games, Beryl Graham observed that installations of interactive new media works were most effective when they not only facilitated interactions between the visitors and technology, but between the interacting visitors and the larger audience. Further, a study of motivations for viewing and subscribing to Twitch streams reveals that while the social and recreational aspects of videogame streaming are the primary motive for many in the audience, seeking information about the best way to play certain games or new games they may enjoy is also a significant predictor of how many hours these viewers will watch. This demonstrates crossover between watching and gaming.

On the other hand, you could argue by not playing these visitors miss the point of an exhibited videogame by not having an authentic experience of it, the implicit offer of the museum space. From this perspective, the ideal solution would be to increase the accessibility of these games through altering control interfaces, or possibly tweaking the games themselves. However, this approach may alter the “original object” trying to be preserved, and even more didactic material or assistance from gallery guides can become impractical for both the institution and the visitor to deal with.

There are many reasons people choose not to play the videogames in a museum exhibition related to familiarity, confidence, availability and ability. But it is also an important component of how people who are avid players also choose to experience them. There are not inherent “spectators and participators” that enter a gallery, instead the boundary between these two states is porous, and most visitors will move between both.

Nonplayable display modes that feature glitches or self-playing mods also serve as a first step to making process more visible in exhibitions of games, as they reveal the structure on which virtual worlds are built. Play modes or installations that focus on performance and spectatorship also foreground the urgency for developing more archival methods, and archives which incorporate play and community practices, elements that contribute to how the game is played and why it is important culturally. And all of these display practices go beyond emulating the code. The popularity of various ways of watching or playing with games that don’t match our imagined ideal player don’t mean that these practices should be corralled into correct play, but that we should reorient our approaches to see these behaviours as relevant elements of the videogames we put on display.