Posted by: Em | SEP-16-2019

Chulip was, almost inexplicably, distributed in the US as a “GameStop exclusive” in early 2007. It was very late in the life cycle of the PS2, and the game did not look like most of the titles that were keeping interest in the console alive at that point. Its comparatively simple graphics, odd premise, and finnicky gameplay, where the means of progressing were often unclear and sudden death descended on your hapless character regularly, especially early on, meant that the game was essentially trashed or at the very least given the “so bad it’s good” treatment from most mainstream magazines and review sites when it came out. All of these factors probably contributed to the fact that I was able to buy a banged-up used copy with layers of increasingly desperate price stickers in the corner from my local GameStop late in 2007. I don’t remember if the one that was on the top said $2.99 or $5.99 when I got it, but it was probably the cheapest videogame I had ever bought at that point, before small transactions on games like deep Steam sale discounts and passing a few bucks to my favorite small-scale creators were much of a thing.

Chulip is on my brain again because, after last week’s Nintendo direct, there was a surprising amount of hype around what seemed to be a fairly niche announcement, that Moon: Remix RPG Adventure is finally getting an English localization with its upcoming Switch port. Yoshiro Kimura, the director of Chulip, was previously a designer and writer at Love-De-Lic while they were making Moon, and has gone on to work on many Onion Games projects like Million Onion Hotel and Dandy Dungeon. The Moon announcement has led to some renewed interest in the Onion Games catalog, which is great, but the title that is the main reason I follow Onion Games’ work is Chulip.

To me, Chulip is not “so bad it’s good” or “so weird you have to try it.” These are frames any Japanese videogame which differs even slightly from Western audiences’ expectations seem to get sorted into which shut down deeper, more committed appreciation as well as acknowledgement of the deliberate creative choices of the games’ developers, attributing it all to “wacky Japan.” Chulip is not just a “good videogame,” which to me is a boring category to aim for. Instead, it is one of the few and far between works that has such a powerful pull/mystery/vibe/cohesiveness/whatever, that I have to conclude that videogames really are a compelling form, for better or worse. It is a work that epitomizes what intrigues me about videogames, the feelings I chase when I decide to play one.

In Chulip, you control a young man who has moved to a new town, and wants to share a kiss with a young lady who’s his new neighbour. When you go for it right off the bat, she flatly rejects you (and knocks you flat on your back, which becomes the standard punishment for an unearned or ill-timed kiss). The problem of earning her love will not be solved by the more codified forms of videogame romance that are now often half-heartedly deployed as evidence for the “maturity” or “diversity” of games; there is little in the way of dialogue trees or bond point mechanics here, but instead you must share a kiss with enough members of the small town you’ve moved into to prove your respectability to her.

The idea of gaining respect from a community as the primary goal of a game is unusual in a medium where NPCs are far more often disconnected signposts, resources, killable, maybe friends if you want them to be, but generally with few real consequences for ignoring them. Requiring that the player instead carefully incorporate themselves into a community, not just as one potential way of playing but as the win condition, is an element of what makes Chulip’s world have such a strong draw. Observing the abundance of carefully placed details, character routines, and social relationships is vital to winning every kiss, not just a fun option. Chulip fully commits to a potentially nonsensical mechanic, which creates a sort of tonal effect very specific to videogames, and supports this mechanic with a dollhouse-world of train schedules, underground residents, collectible cards, a run down cinema… a mysterious and rich living diorama.

That the mechanic through which you reach the game’s goal is via a big, fat, on-the-mouth kiss is interesting too, because the ability to kiss and who you can use it on is also often a tightly controlled element of the few games that include it at all. These kisses are platonic in comparison to the final kiss you want to share with your love interest, but getting them still takes on an overriding romantic atmosphere. In Chulip, a kiss is a symbol of a problem solved, some sort of (often secret or concealed) desire realized. Observing your kissee’s behaviour, often while hanging off to the side or peering through a crevice, is a must. While alone, or at least thinking they are unobserved, they voice their dreams, their sorrows, their frustrations. Solve their problems, or carefully approach in the joyful moment when they want to be kissed, and your smooch will be successful, causing your heart, and reputation, to grow.

“The Rules of Love are the rules of the universe, the rules of the universe are the rules of Long Life Town”

Despite these kisses being in service of a higher and more explicitly romantic goal, they still have the trepidation, excitement, care and tension of the build up to a romantic kiss. Each kiss is earned by learning to understand the other person (or Godzilla, or Onion Lady), satisfying their need or being present at the right moment, and fosters a connection with each of the town’s strange inhabitants. Naturally, the kiss with the town’s single policeman, then, comes across as extremely romantic.

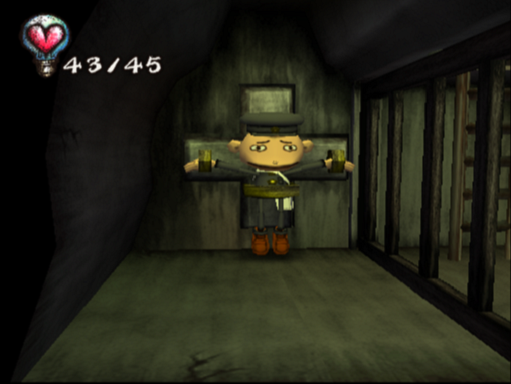

Policeman typically stands near the center of the town, providing a point for you to access the lost and found during the day, as well as present him with the personal cards of any other member of the community to find out their criminal record. But no one in town really has a criminal record… he’s pretty bored. And as the sun goes down, his usually cheerful demeanor goes stiff, his eyes turn to floodlights, and he patrols the town, shooting at anything that moves in his line of vision. It’s as if his Freudian sublimated impulses take over during the period when he’s supposed to be dreaming, indeed, at the local doctor’s office he has been diagnosed with the disease “toohs annaw.”

Around a third of the way through the game, a scenario may arise where you need to acquire some Sweet Potato Wine, a local specialty, to make an offering at the nearby Worldly Desire Temple. When you take the wine coupon to Julie’s bar, you witness a fight between her and her “loser” alcoholic husband, Goro. Julie blames his lack of motivation and drinking habits for why your love interest, their daughter, ran away from home, and this is not taken well by Goro, who chucks the wine bottle at her head. Policeman, hearing the sound of the argument, arrests Goro for assault and sends him away to the “graveyard,” where criminals who have accrued 3 crime stamps go.

Performing one arrest only whets Policeman’s appetite for another. Almost like a courtship dance, you have to perform three crimes in plain sight of Policeman to satisfy his desires. First, buy some cigarettes from the shop outside the train station (the shopkeeper helpfully informs you that you can’t smoke unless you’re 18, but sells them to you anyways), and smoke them in front of the police station. Then, go to the public baths but sneak out after taking your clothes off, streaking in front of the police station. Finally, open Julie’s bar safe and take out her special hairpin, and present it directly to Policeman, being sure to specify that you did, in fact, steal it.

“Your crime stamp total is now 3. Have a nice rest beneath your tombstone. Here’s a farewell kiss.”

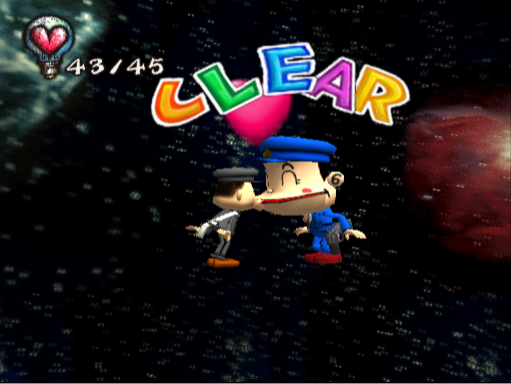

After the kiss, emphasized with a swell of romantic music like every other in the game, the next we see of the protagonist is him bound to a crucifix/gamepad, but then mysteriously released. By figuring out a fairly straightforward glyph puzzle on the prison walls, he can also easily free Goro from the decrepit, ineffectual, 2-seater prison, and Goro apologizes to a waiting Julie. Julie also kisses you for helping to resolve their fight, and gives you a return train ticket home. Everyone returns to Long Life Town.

“My vision in blue, I call you from insi-i-ide my cell”

The fantasy of kissing the cop in Chulip has a similar tone and theme, in its lightness but simultaneous undeniable romantic frisson, to the 1976 the Blondie song “X Offender.” Chulip takes the perspective of the socially alienated adolescent (at this point in the game you are still not likely to have gained enough respect to be truly accepted by the community, and your love interest), and “X Offender” takes the perspective of a sex worker, but their stated goals of getting with the cop that arrests them are the same. The original lyrics for “X Offender,” which Debbie Harry revised, were written by Blondie’s bassist, and were about getting busted for having an underaged girlfriend, which may have fit with the rock n roll mores of the 70s, but doubtlessly would have aged even worse.

These fantasies are uncomfortable because they risk masking or making light of the brutality and terror exercised by police and policing. “Juvenile offenders” (being the kid with two crime stamps), and sex workers in particular are two of many groups who are prone to invasive and abusive levels of scrutiny from police, and for whom the long-term consequences of any “punishment” brought on by this attention by far outstrip the perceived offense or damage caused to the community, which is usually practically immaterial.

However, I feel like these fantasies are functionally different from the equally ridiculous depictions of “good cops” in procedurals and comedy shows. Romantic fantasies present a situation, however passing or superficial, where policing has been defanged to the point that it is just the context for a game of flirtatious cat-and-mouse (see also: the entire Lupin III series, and resulting homoerotic fan content), or the more romantic in tone yet platonic in goals and realization communal love that is the primary mechanic of Chulip. Policing being ineffectual to the point where its stakes are no more serious than the affective ups and downs of pop tune romance and desire at least partially thinks through and past the present situation, where the maintenance of hierarchy, prejudice and power within capitalism are seen as the necessities which justify ever-escalating policing (friendly-faced or not). Chulip’s fantasy policeman is not just an entertaining instance of a mildly scandalous smooch; it makes sense in the broader whole of the game, a utopia of kisses where the rules of the universe are the rules of love instead.