Posted by: Em | MAR-19-2020

Image Source: Tumblr and The Silver Case

The final Nintendo Direct before the release of Animal Crossing: New Horizons revealed that animals will have to apply or be invited to live on your island in pre-selected lots, rather than their usual anarchic comings-and-goings which, in past instalments, would often flatten the most carefully-laid orchards or flower beds. Words like “perfectly planned community,” “services” and “development” were enunciated by a warm female voice, and signalled more significant changes to the series’ typical features. Players can now alter the terrain of their island, chipping away cliff faces and redirecting rivers. Further, Mr Nook is now a CEO, makes loans and runs a shop in his own currency, “Nook Miles,” which are earned through contributing to island life and simulated social cohesion. There’s even a “passport” item, which ominously implies a border control apparatus in a game series where you previously hopped off a train to live in a new town with nothing more than the randomly generated face and shirt given to you.

The Animal Crossing series has, in general, arced towards more control over the development of the player’s town, from the random placement of shops being replaced with a separate “main street” and addition of a wide variety of public works projects in New Leaf to the total “desert island” starting point of the upcoming New Horizons. While far from being a complete “god game,” it has gone from the experience of moving into a new place which mostly sets the parameters of the lifestyle and possibilities for you there, to fostering more of a design perspective, thinking about making and managing a town, its people (or talking animals) and its resources as a whole. You can make things look a lot nicer, the environment can more greatly reflect you, your whims, desires, personality, but this is a trade that costs the game a lot of its opacity and resistive power that made it so compelling that I felt like I could always encounter something new when I booted up my GameCube almost daily between 2002 and 2004.

New Horizons hasn’t gone so far to introduce an entire, disembodied an omnipotent “city planner” perspective, as in the Sim City series, yet the talk of permits, reserving lots, and even the ornamental hard hat your character gleefully dons when building paths, rivers and cliffs moves the player closer to seeing themselves in that role. In fact, city planning simulators and other forms of simulation games have often been theorized by computation and games industry boosters as fun ways to educate future planners, politicians, and citizens in general about issues their towns and cities may face and potential ways to resolve them.

Kevin Baker has already written an incisive essay on the problems that arise from this assumption, referring back to Sim City and the book Will Wright based many of its simulated elements and rules on, Urban Dynamics. The reduction of a city to interlocking systems and equations that can be optimized towards growth is a seductive parable, but it’s important to note what this depiction deliberately excludes. While “traffic” is an abstract blight that can affect your city, parking lots or methods of mass transport do not play a major role. Only later iterations incorporate waste management, and, within the simulation, sim citizens do not really have any demographic qualities, or resulting desires and needs. In essence, these simulations tend to exclude anything that is undesirable, unglamorous, or simply too complex to reduce to a set of equations from the question of what a successful city looks like.

The fantasy of a perfectly planned, optimizable city deliberately erases these concerns (in some cases Animal Crossing has moved in the opposite direction of the SimCity series, since the first game had a dump which has vanished in subsequent entries), and then presents an answer to the problems of housing, politics and public life that doesn’t consider them. The answers that Urban Dynamics presented, and Sim City goes on to present is a neoliberal program of non-interventionist actions that simply create “initiatives” for businesses to “revitalize” areas, where welfare programs and public services are rolled back in favour of tax cuts for the wealthy “job makers.” Influxes of certain populations are deemed lucrative, while other forms of immigration are marked as undesirable and necessary to curtail.

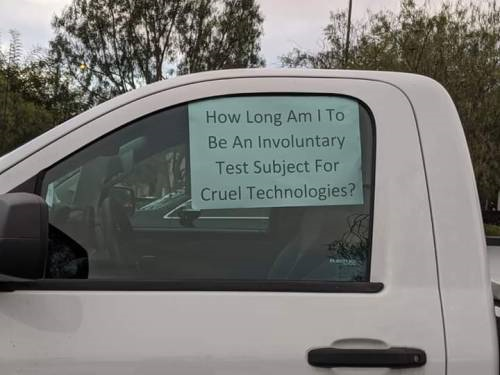

The manifestations of these ideas may seem less literal or consequential in the Animal Crossing series, but they still color how players are encouraged to see their town and community. The introduction of a “passport” item, additional controls on multiplayer behaviour, and the fact that animal villagers must either apply or be invited to live on your island may be an attempt to formalize systems that players previously would use to “trade” desired villagers and determine where they moved, but in practice reads undeniably brexity in the age of “points-based” immigration and increasingly byzantine surveillance and restriction of movement. For me, at the moment, I find myself having to pass on Animal Crossing, it’s now the furthest thing to comfort food.

From the same Silicon Valley context where Maxis propelled itself to be one of the most influential software companies of the 1990s, plenty of start ups and venture capital backed business proposals have emerged that are, conveniently, highly amenable to these perspectives on how to build and re-build cities. The sort of private partnerships that city councils salivate over and compete for to try and please tech corporations like Amazon and Google grimly prefigure that now CEO Nook is sitting next to Isabelle in your new town hall. The justification of these often wasteful, ineffective, extractive (whether in terms of surveillance data or money that would otherwise go to local initiatives) and unethical practices comes from ideas that are put forth in computer simulation, and a simulation that starts on a fantasized empty space or deserted island at that. History is always messier than this, and the way these systems play out far more complex and unpredictable, in a way that directly providing resources to people who need them, demonstrably, isn’t. Still, the fantasy of a perfectly optimized city is a potent one, for tech entrepreneurs, politicians, and law enforcement, precisely because it concentrates wealth, power and influence at the top, with whoever gets to be the player.

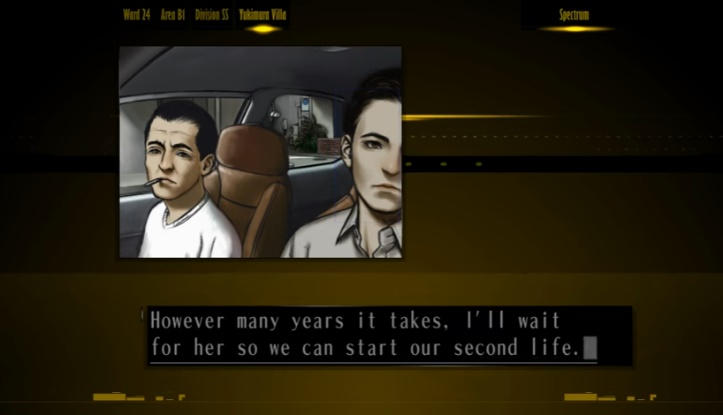

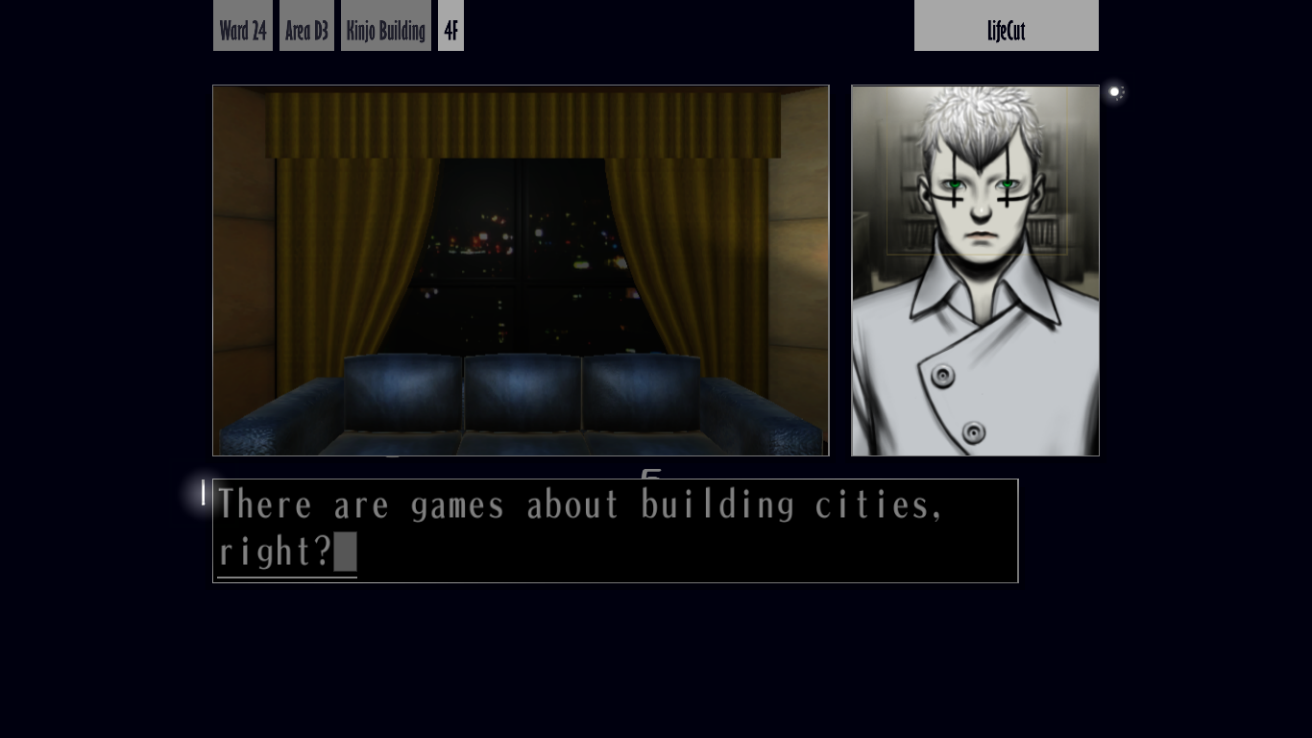

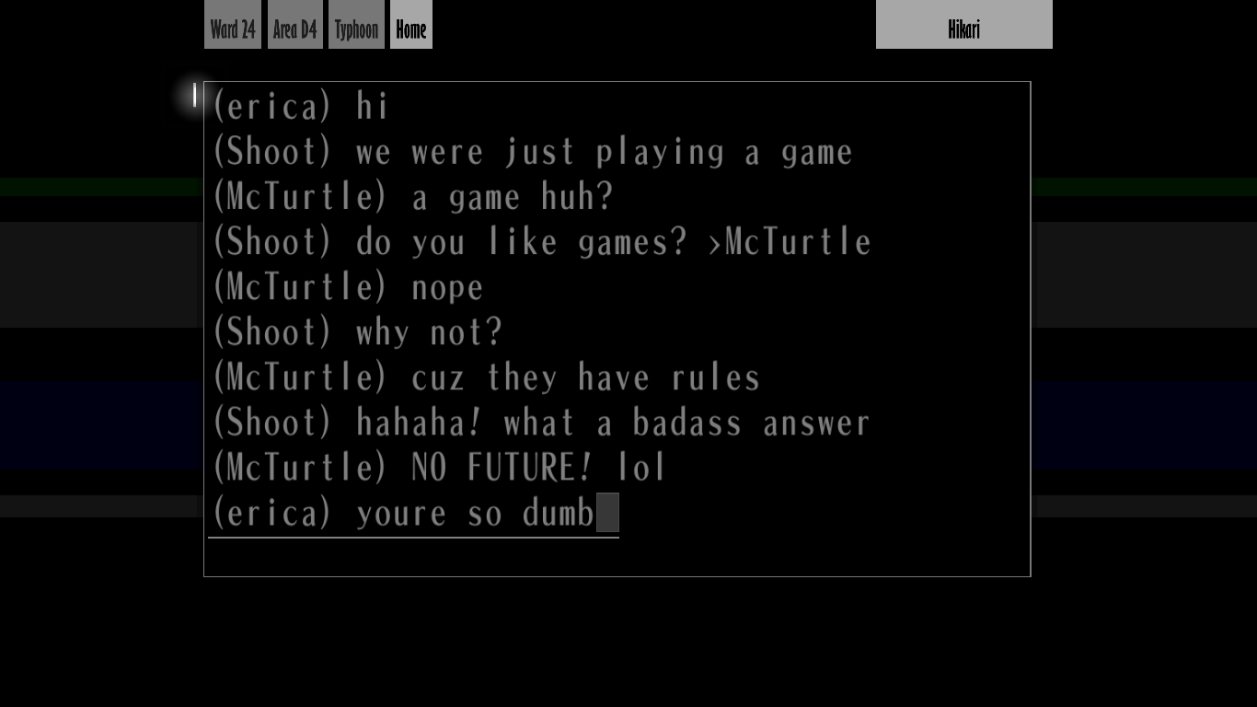

Towards the end of the 1999 visual novel The Silver Case, you meet up with an information broker who uses the idea of a videogame about building cities to convey the structure of the ward where the game takes place, and subsequently, the motivations behind the series of bizarre crimes and murders you have been investigating. Ward 24 is an entirely planned city, with all of its inhabitants specifically selected and monitored constantly by advanced technology. Typical political parties have little sway in the area, and instead the current mayor represents an alliance between two of the three NGO syndicates that play a major role in city life, representing redevelopment, law enforcement and technology companies. Social hierarchy is maintained by a wealth gap, but the game is careful to also point out that there is, more importantly, a parallel information gap, the wealthy and powerful know much more about the workings of the city and the activities and histories of its inhabitants than the average citizen, and they maintain their power by exploiting this privileged info.

The three major syndicates sometimes have conflicts in their power games, though, and despite apparent cooperation will resort to brutal methods to retain their power and increase their capital. This is secretly the source of the cases pseudonymously attributed to the mysterious serial killer “Kamui.” Kamui, and a female equivalent, Ayame, are not singular personalities but a way to describe activated “shelter children,” who were raised in a controlled way to be ideal ward citizens. These ideal citizens are not passively compliant, but instead can be made to kill on reflex for interests of these various syndicates. As a way of maintaining control, or initiating conflicts or political assassinations, the population of Ward 24 has been seeded with over a thousand of these individuals.

And this is only one of the many conspiracies of dystopian technological and political control that intersect with the Heinous Crimes Investigation Unit that the player character is recruited into. Sumio, a fresh-faced and seemingly by-the-book new hire is arrested after secretly committing a series of kidnappings, bombings and murders as revenge on a wealthy family that destroyed his hometown with industrial pollution, and abandoned their young daughter, his childhood friend, as a decoy while they escaped, leading to her murder during riots that broke out after the revelation. Hachisuka, the office’s forensic analyst, doesn’t live to discover that the man she thinks is her father, the mayor of the 24th Ward, is actually her grandfather, who discovered a method to regain eternal youth and murdered his own son to take his place and extend his political power, setting up many of the systems that led to the Kamui-related murders. Instead, she awakens as an Ayame shelter child, and gets gunned down by a co-worker when the Heinous Crimes Unit itself becomes the next pawn in syndicate power games.

The horrors this social control leads to in the interests of growth and consolidation have the tone of a sort of futuristic Saturn Devouring His Son. Amid all the atrocities set in motion in the interest of maintaining the 24th Ward as a perfectly controlled city, there is a recurring motif of the politically powerful, those who are building the city as if it’s a game, hoarding money and information and abandoning their responsibilities to fellow human beings and subsequent generations, often literally symbolized by the moment they consume their own children in the process. Goichi Suda’s conspiratorial and dreamlike narrative, in the format of a rather “linear” and barely “interactive” (in the typical sense) visual novel ironically far outclasses games that present cities as a system to be moulded by a remote player figure in representing the problems of cities with any realism.

The Silver Case ends with Kusabi, the veteran detective, and the mute player character meeting in a café for coffee after the complex fallout of the incident which simultaneously revealed the extent and complexity of the 24th Ward’s corruption, and resulted in a string of double-crossing murders that wiped out almost all of the Heinous Crimes Unit. The mood is solemn, yet Kusabi speaks with hope and conviction. “Let’s take our time and get rid of all of them,” he states, referring to the filicidal and wealthy syndicate leaders, who have no problem exploiting and controlling their own children and grandchildren to continue to wield their power over the cityscape. It’s a grim business, but through the revelation of these shadowy movements of power, often swept out of view or made invisible in day-to-day life, the knot can begin to be unravelled.

“It’ll be a new age soon. Aren’t we lucky?” Kusabi goes on to say. “To be born in this age so that we can witness such a wonderful moment.” His words may be even truer than he thinks. In a post-credits scene, it’s revealed that at that very moment, the Mayor of the 24th Ward who has orchestrated the social control that feeds into these cruel systems, was murdered by a new Kamui who had evaded top-down control, leaving the player with a tantalizing “To Be Continued…?”

I think of the simultaneous hope and chaos implied by the ending of The Silver Case, I also think about how Kentucky Route Zero recently ended in an ex-company town that had been turned into a sort of artists’ commune barely hanging on by its fingernails through a natural disaster, but persevering, and I think what I would like the future of my potential Animal Crossing: New Horizons planned island community to be, if I get over my distaste for these new features and end up buying the game. Will Nintendo, one of the most prolific and friendly-faced copyright landlords of the media landscape, offer a future downloadable event update where you can agitate your animal friends into running Nook and his Nook Miles program out of the community created by your labour and collaboration, seizing real control of your virtual lives? Probably not, but I can dream.