Posted by: Em | NOV-12-2019

Catching the tail end of The Fly when I was too young to process it had the unfortunate effect of the name “Cronenberg” giving me an outsize feeling of dread and fear well into adulthood. But I finally “got over it” to an extent, and was cajoled into watching eXistenZ on Halloween. Afterwards, my thoughts were typical: “that film ruled” followed by an urge to look up any interesting information on it with imdb. While skimming some of the user reviews I was surprised to see the sentiment (framed negatively) that Cronenberg did not accurately represent VR games or anything happening in videogames in general, that the presence of videogames was a sort of topical container for Cronenberg’s usual themes. This idea intrigued me, because I so strongly disagreed.

I could also easily see how people eager to discuss videogames in a more nuanced way would point out the violent, gory content in the game of eXistenZ and the way it’s presented as hypnotic and compulsive are drawing on typical paranoid and out of touch popular fears about videogames. Yet people who dismiss these fears often seem naïve as to why these narratives keep coming back. To me, eXistenZ may not be representing videogames accurately in the first-order sense of representation, but there is still something very cutting and very true about what happens on the screen, how the characters talk about and take to these strange devices.

A Videogame Dreaming of Itself

Sure, eXistenZ does not really represent videogames, or what they have actually been at any point during their history. But that would be kind of boring. I can already bore myself to death several times over playing the apparently very boring AAA productions on offer this year. eXistenZ is not representing a real or fictional videogame, but representing a certain metagame, in the sense that Stephanie Boluk and Patrick LeMieux use the term, a sort of magic circle and set of rules for the work/play of defining and discussing videogames in general. An example they cite is the “standard metagame” for playing commercial games, the presumption that a videogame is, for example, played with a standard controller on a console or high-end gaming PC with certain technical specifications. The expectation that you’re probably young, middle class, white and male informs the aesthetic of the hardware, the content of the games you play on it, and the culture around the game that is tolerated online and in irl spaces. You have free time to play, probably in a designated “gamer chair” or living room space, and a focused and competitive attitude towards online play, without exploiting glitches or unusual playstyles. Give too much indication that you might not have access to all of these features and align with these attitudes and perspectives, and your chances of being on the receiving end of some voice chat abuse drastically go up. Conform, play properly, or risk being a spoilsport, cheat, and so on.

The metagame of talking about videogames is also a set of ground rules denoting goals and out of bounds areas. A lot of this conversation’s foundational literature is based on premises we don’t necessarily have to work from or even maintain, that videogames are systems, they’re new but they also have the most things in common with both the pre-digital forms of games that exist and a generalized concept of play, that they offer agency and choices, they are interactive, and that designing them in the direction of increasingly immersive, complex and flow-y loops of action recognizable as “gameplay” is the ideal direction of videogame creation. Like the standard metagame above, this metagame also becomes invisible; it doesn’t need to be clearly stated when calls for papers, job listings, and journal review boards do the work of excluding anything that has become unfamiliar to a self-replicating process.

It’s easy to feel like a marginal character within this game, when these presumptions simply have the benefit of being said early, at scale, and confidently enough, when they are what has shaped not only what people expect or want to hear, but what venues to say it even exist. Trying to bring a different approach to the table, especially one putting videogames in a larger context of art or culture or analysis methods is seen as a spoilsport move too, as the laughable claims that perspectives informed by the historical study of film and literature were “colonizing” the “exceptional” and “unique” frontier of games studies demonstrate.

The vision of videogames which this process often serves to maintain is premised on the idea that videogames have specific, singular qualities, that making connections to other forms or placing them in a historical context beyond a narrative of escalating technical and design prowess somehow lessens them. Not only is it savvy to pitch these qualities as exceptional, it’s a bonus if you can come up with some reason these qualities are particularly desirable or useful. Cronenberg seemed to, consciously or not, be aware of this ever-present process of inventing and maintaining hype even in 1999.

The observed truth of one of the parody games seen in a videogame store scene was what convinced me Cronenberg was really talking specifically about videogames, and it goes beyond mainstream videogames’ affinity for shock-value violence. Hit By A Car depicts a man looking ecstatic as he bounces off the hood of a speeding car, and promises to put the player “in the driver’s seat!” Whether your fantasy is to be run over by a car or accidentally hit a hapless pedestrian, the packaging screams that it will deliver this experience, with a maximum of “fun factor” and “graphical WOW!” Cronenberg’s treatment of videogames is to consider, for a moment, that this self-presentation is actually true. At what point does videogames’ dream of itself begin to become a nightmare?

Butt Stuff

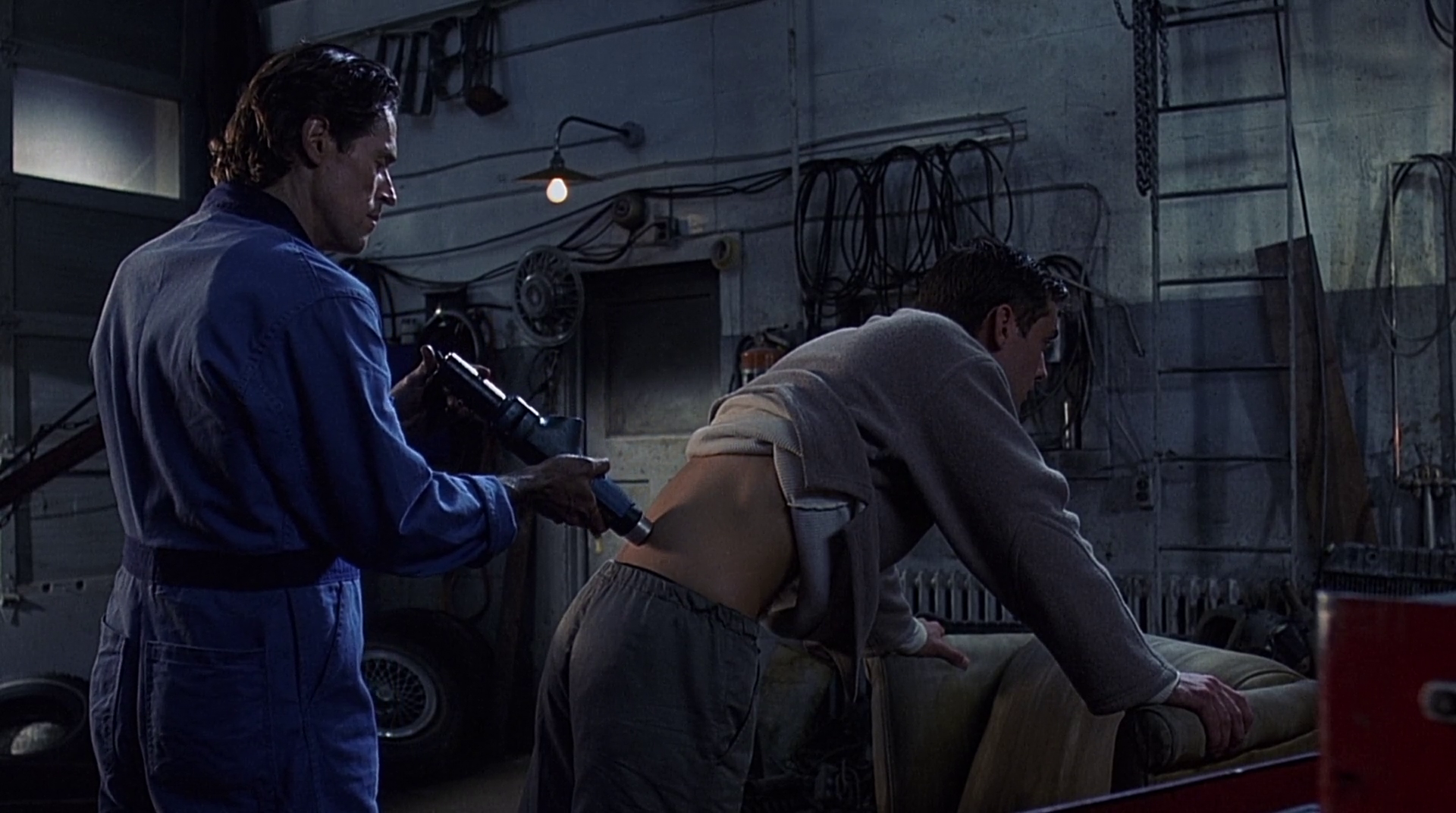

If Jude Law shyly insisting that he has a bit of a phobia about his body being “penetrated” (surgically, technologically, of course) in an overly-earnest American accent is potentially your sort of thing, this film does not disappoint. When a test of the new eXistenZ console is interrupted by a man rushing the stage with a gun made out of a mutated jawbone that shoots teeth, he attempts to kill Allegra Geller, a mysterious and reserved game designer. Wounded, she is forced to go on the run with Ted Pikul, Jude Law’s character and a security guard for the game company’s secrets. But soon it comes to light that Ted urgently needs to be bio-ported; the eXistenZ console has potentially been damaged in the attack and Allegra needs to test it with another person to make sure her work is still fully intact. The relationship of the characters to the game consoles from this point on is sexual in every sense. While this is most explicit through the tactile operation, the writhing and sighing flesh of the game pods, the application of spit or lubricant to the cords before insertion, it’s also signalled and commented on by elements other than the grisly prop and SFX work. Heteronormatively speaking, the player is the receptive partner to the console, rather than the active one.

Characters wince and swat away any unexpected prod to their bio-port, and it’s talked about with a tone that is simultaneously facts-of-life scientific, and hyperbolically sleazy. It’s as normal as getting your ears pierced at the mall, but on second thought, was having a teenager clamp a low-quality rhinestone stud through your ear at Claire’s also kind of a bizarre biotechnology? The normalization of this (with, I’m sure, a much higher failure or infection rate than the bio-ports’ infinitesimal percentage) is the sort of beauty-as-pain we expect women to grimace through or even idealize due to their subordinate place in the sexual hierarchy and similarly narrowed horizons. Making this the price of admission to a videogame, which promises the appeal of power and agency by contrast, seems incongruous.

Agency and power are what videogames say they offer, and feelings related to these concepts are doubtless what a lot of people get out of them, or think they will get out of them. But these qualities are far more illusive than the language so often used to describe what games are about or do: choice, agency, and the eternally-humanistic play, by this point almost a good in itself, maybe even a human need… But videogames, for the most part, are dragging us along more than we are working on them. Limited, artificial choices, and control schemes that have only a slip of the finger between speaking to an NPC and blowing their head off are meant to make us feel free in the midst of all the other things there’s no real choice in. The player is expected to fully utilize each “freedom” they are granted gratefully, rather than ask why the actual actions that can be taken are so constricted.

eXistenZ plays out the constructed limitedness of games, so often brushing intrusively against the exhortations that you’re powerful and free. The image of a body plugged into the game console, limp, dreaming and penetrated, regularly haunts the virtual fantasy down below, but this fantasy is also disempowering in its own right. The NPCs Ted and Allegra encounter, which we later find out are players on other levels of the game, manifest as broad stereotypes, who often respond only to specific phrases or requests, and are totally naïve to anything else. Further, many segments lead to a situation where the limitless agency and freedom promised by this ideal, fully-immersive game is jarringly rescinded.

Giving in to their “game urges,” characters are forced to watch as their bodies seem to independently engage in acts that disturb and repulse them, mechanical foreplay without desire in a seedy storage room, single-mindedly devouring an entire platter of slimy, mutant creatures, murdering a waiter who’s been nothing but pleasant and accommodating. It’s an effective way of demonstrating how the supposed freedom of videogames, allowing you to superficially reshuffle constrained and often highly codified actions, is utterly piecemeal, and yet this limited definition is “what counts” in discussions of agency and videogames’ uniqueness. The variety of perspectives, actions and themes that already existed in “static” media like literature, for example, don’t qualify.

Bleeding, Squirming Chunks

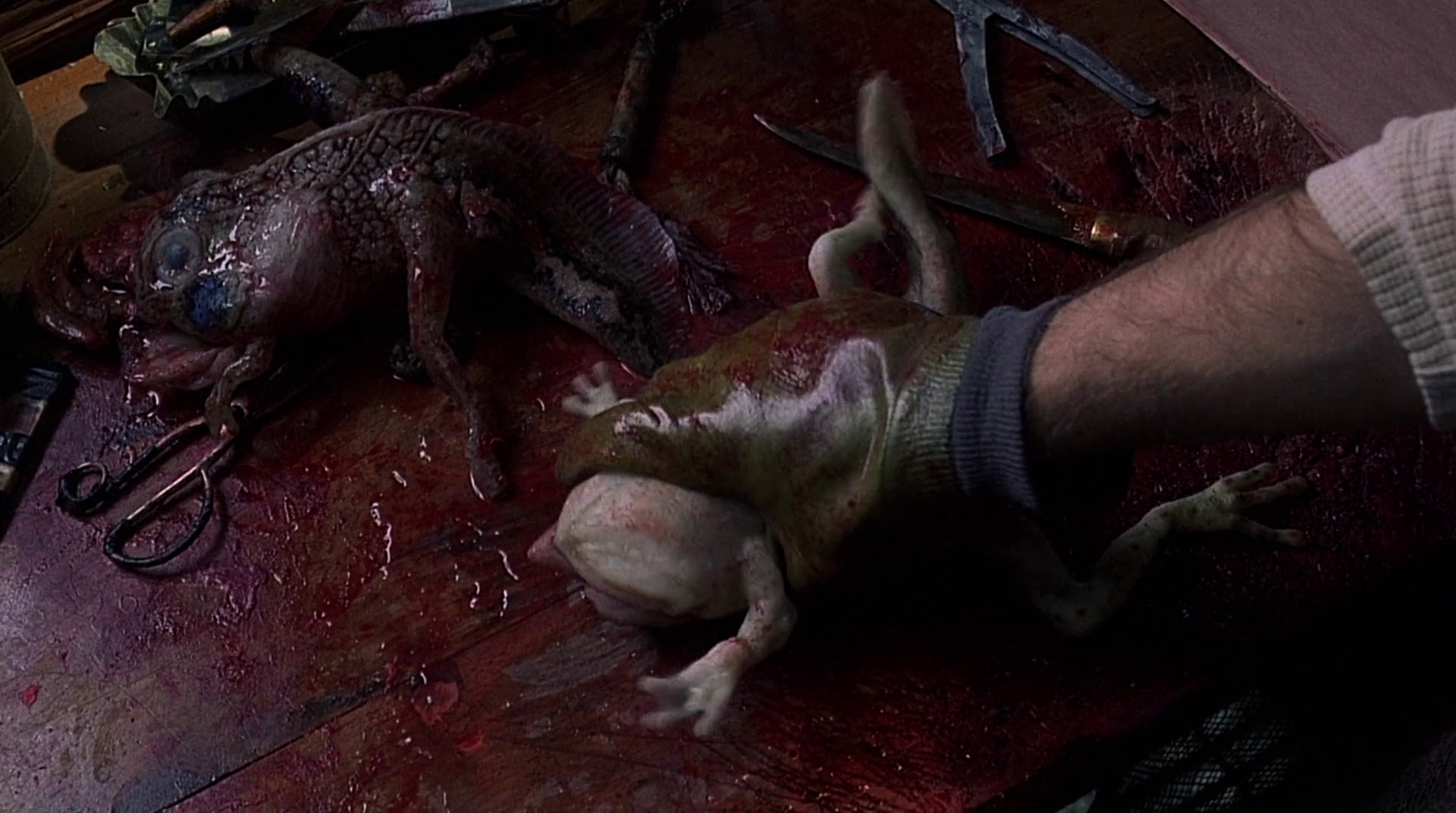

The defining “Cronenbergian” element of the film are the fleshy, throbbing pods that make up the eXistenZ game console. The way they weirdly twitch to life while the player attached to them with an umbilical cord to the bio-port enters a still, trancelike state is unnerving enough, but over the course of the film we also become intimately familiar with how these consoles are made, what their guts look like. A major sequence of the game involves an espionage mission in the factory making the very same consoles the game is being played on, and of course Ted fumbles his way through the brutal gutting of the mutant amphibian creatures harvested for the pod’s materials while bluffing that he’s been “trained by the best” to successfully infiltrate the factory, mirroring my initial experience with any of the Metal Gear Solid games. The process of gathering these mutant creatures, harvesting their organs and assembling them into pods is shown as filthy and unwholesome at every stage. And this is not just within the scenario that the eXistenZ console dreams up. In one scene, we see Allegra’s pod going through some hands-on troubleshooting from a friend they crash with, and Ted comments that the bloody scene looks like an operation on someone’s pet dog.

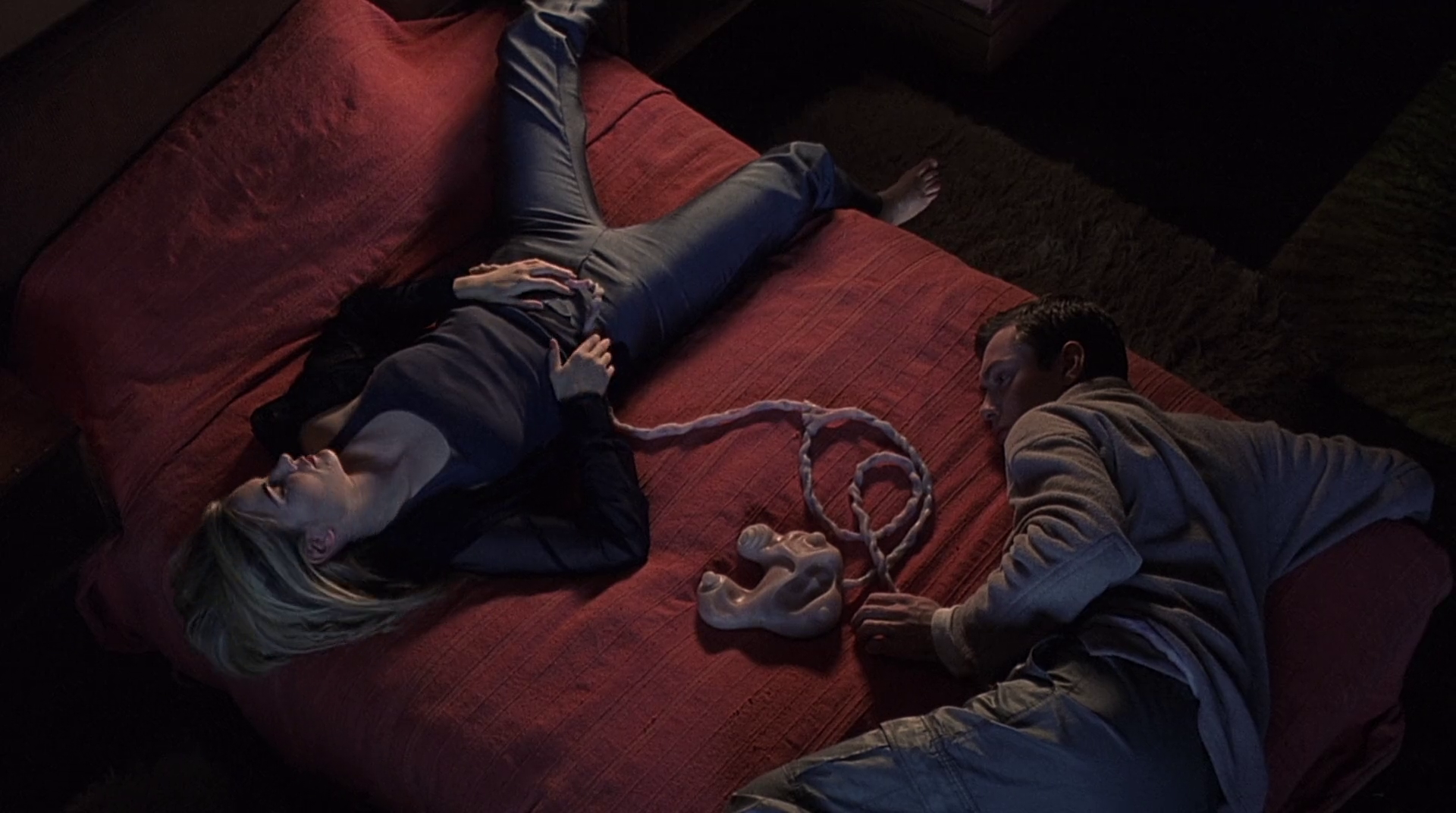

Besides the sexual overtones another visceral metaphor in how the game consoles work is maternal, but this seems to be a two-way or at least ambivalent comparison. Allegra tends to her game pod obsessively and cradles it like an infant, the console runs on its player’s energy and metabolism, and getting a fresh bio-port apparently knocks out the feeling in your legs for a bit, just like an epidural. But when the pod is activated, it’s the image of the players, connected by umbilical wire and curled on their sides on a red-satin hotel bed, that becomes foetal. The slipperiness of this dialogical relationship, we create and tend to the game which in turn, also plays a part in birthing us, is especially pronounced in a gruesome scene where, cutting the umbilical cord to free Allegra from having plugged into a distressing, infected pod, Ted causes her to bleed to death.

By plugging into games we become imbricated in a variety of systems of violence and brutality that goes beyond their representation of violence, though it’s worth noting that weapons manufacturers and both the US and UK military industrial complex all act more decisively than the general academic or critical discourse in responding to the popularity of these representations. You could read the graphic dismemberment of countless hapless amphibians as a literalization of the repetitive violence and gore in videogames, but more interestingly, and given the fact that this image is placed in an industrial context, an element of videogames that is all too often vanished at every level like so many Christmas elves, these poor gutted frogs can be easily read in a variety of interconnected ways.

Their “labor” is what makes the consoles themselves work, in the form of their literal organs being extracted and inserted into the games. They are depleted and tossed aside, not only like so many precarious and crunched game studio employees who don’t attain the glamorous and creative visibility of a “famous game designer,” but also the exploited communities along international rare earth metal mining and supply lines, and the workers in massive factory complexes that assemble the consoles and accessories for sale around the world. The creatures’ mutations also suggest the environmental consequences of proliferating personal technology, from the very literal effects of rapidly obsolesced e-waste and plastics on groundwater systems, to the more subtle dread of an uncontrollably changing world, as the technological demands of AAA sheen, distribution and streaming, even “cloud gaming” become unfathomably unsustainable in their hunger for human and more straightforwardly carbon-based energy…

In contrast to the clean, smooth, glass and stainless-steel surfaces and modelled plastic minimalist curves of most luxury tech, as well as the contexts it is presented, advertised and demonstrated in, this factory is depicted as grimy and haphazard. It’s also interesting that it’s depicted at all. The twitching of the biological consoles on the first level of the game is unnerving because we are used to technology being smooth and inert, clearly non-living. But beyond that, Cronenberg also wants us to see these tech marvels bleed. The black box of proprietary consoles and technology that close off knowledge of inner workings, the source of these strange gifts handed to us fully formed by “capitalist innovation,” keeps us alienated from the unsavoury practices at every level of their production… it keeps us from even considering production in the first place. The hellish console factory is the dream of a malfunctioning game console, tabulating the violence tucked away across its lifespan and spitting it out as a gruesome symbolic nightmare.

The weirdness of the maternal reversal also captures the often seemingly inescapable contradictions of this situation. While new technology once appeared as innocent and shiny as a baby to coo over, it’s been naturalized as an almost necessary part of modern life. We find out worse and worse things about it, but it feels more and more impossible to cut the cord. Perversely, in the midst of a lack of stable employment due to neoliberalism and venture capital cutting every corner to the blood-drawing quick and gig-ifiying anything they can, videogames become the site where capitalist social reproduction, the belief in the value of work, the mental satisfaction of a job well done, has to take place. What was once the coveted fantasy of escape becomes an all too banal trap. Who makes who?

Unhappy Consciousness

In a basic sense, Hegel’s concept of “Unhappy Consciousness” is a consciousness that is aware of an unreconcilable contradiction within itself. So if the core theme of eXistenZ is videogames’ necessary self-perception, and, perhaps more broadly, the self-perception of novel technologies in general, the film represents a self-image which is faulty and can’t hold, but at the same time must hold. This is why the game cycles through multiple levels of consciousness, multiple scenarios, multiple tries to create the ideal game with no problematic attachments to superstructure or buried unconscious. Does it matter, or can we tell if the final world they wake up into is the “real” one? Arguably no, because if the game continues to wake up unhappy it will simply roll over and continue dreaming.

The unhappy consciousness of videogames is a sense of contradiction that I hope, but doubt, their most opportunistic boosters possess. These are the people who excel at the metagame of framing their work in a way that pleases the tech-exceptionalism and extractive impulses of present neoliberalism, which directs the flows of venture capital, the construction of disciplines, storefronts, festivals and university departments, and provides sustenance for the most basic form of hype, that there’s just something new and special about videogames. The particular ugly, jaggy tooth-gun that keeps coming back into this chirpy utopia is that if you want to argue that videogames are uniquely able to improve mental health, can’t they also be capable of devastating it? If they’re especially good at conveying positive political messages, can’t they just as easily mislead people?

Alternately, if they truly have no stake in provoking negative states of mind, like addiction, compulsion, anger, and so on, you’re on shaky ground to argue that they can do anything positive either. And are these vanishing returns worth it when the assembly line of industrial videogames is littered with the figurative viscera, of e-waste, of colonial supply chains, of inhumane factories, of crunch? There’s no special effectiveness of videogames that doesn’t also have its own negative consequences; none of the fantasies of power or freedom or new experiences in eXistenZ don’t also pulse with gore, decay and genuine danger. The promise of a power fantasy is swapped out with moments of unnerving disempowerment because there is no way for all of these things, foundational pillars of why and how we study videogames, to be really true at once. Paolo Pedercini has insightfully noted about the concept of “games for change” in general: “If your game or technology really ‘works,’ it freaks me out.”eXistenZ takes videogames at their word, that they work, in a variety of senses, and extends these ideas to their logical conclusion, and this is why the idealistic game designer keeps running into gruesome and terrifying nightmares.

After Allegra dispatches Ted with a bio-port bomb, she wakes up with a slick, modelled plastic VR device on her head. She is seated in a half-circle of connected players, almost identical to the interrupted eXistenZ session where the film began. Gradually everyone comes around, and each connected player is one of the characters assumed to be NPCs within the game. So eXistenZ was a game within a game, a clever contrivance to muddy the waters and add an extra layer of intrigue to a typical last-man-standing style battle. Everyone is friendly and politely impressed, even Willem Dafoe’s excellently creepy and eventually homicidal gas station attendant from early in the film. Two guys sit around answering surveys on devices weirdly prescient of a touch screen mobile phone, and the game developer pulls his assistant aside for a quick word.

“I was very disturbed by the game we just played… It had a very strong, very real anti-game theme. I mean, it began with the attempted assassination of a game designer…”

Before they have time to investigate who these adversarial sentiments might have emerged from, they are approached by Allegra and Ted. What initially seems like a compliment of their game design artistry turns into an assassination. After shooting the game designer and his assistant, they turn on the man who was the waiter in the Chinese restaurant. Almost playfully, but with rush of genuine fear, he asks: “Hey, tell me the truth, are we still in a game?” This could be interpreted as the typical scaremongering media sentiment about videogames, that they thin the veil between fictional and real-life violence to the point that obsessed gamers will unwittingly commit “real” violence without thinking. But what if they are metaphorically still in a game, yet no longer subject to the specific rules and structures laid out by the original game designer? To me, that seems a lot more interesting. Finally something real, outside of these well-trod paths, these presumptions and conventions, can be born, and with a gory splat, of course.