|

|

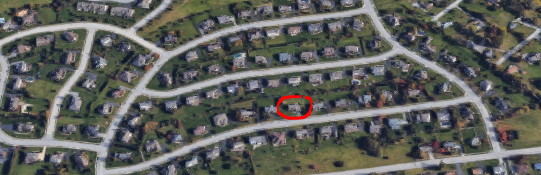

When I was 5 or 6, my family moved from a small, remote house (near neighbors were a farm and a guy who raised emus), to an apartment, and then to one of the first homes built in a new suburban development. |

A big loop of road and the first three or four homes were the only things which sketched out how the entire area would eventually be separated into lots and filled, the rest was essentially undifferentiated fields with occasional large piles of dirt left over from construction punctuating the horizon. I wandered, climbed, got ticks, covered myself in dirt and grass stains, and ripped out the knees of every pair of leggings I owned. But then, on the left, right, and finally directly behind our house in my “extra backyard” these areas were divided up and demarcated, sometimes by more physical barriers, but often just by implication, that I shouldn’t go into “someone else’s yard.” |

|

It didn’t feel like I could wander much, or had anywhere interesting to go anymore, unless I stuck to walking along or riding my bike on the roads, and even then, @bestofnextdoor demonstrates my intuition that some neighbors didn’t even like that. |

|

As this process began and progressed outside of my home, something similar happened inside. We got a new computer shortly after settling in to the new house, one which could read CD-ROMS. It also had Windows 95 on it now, instead of just DOS. It came with games pre-installed, rather than ones that had to be inserted via a floppy disc (or sometimes a series of them!) |

|

The important thing about this shift is that my internal perception of using a computer became primarily spatial. I had played some floppy disc educational games on our old computer which involved moving around, like Mickey’s ABCs where you go to a funfair by pressing letters on the keyboard, but the general use of the computer was conducted via a text terminal, which was still opaque and unappealing to me at that age, even if I had picked up reading pretty quickly. |

But now, when you went on the computer, you moved things around on your “desktop,” and if you had Dogz, your virtual pet could run across it and dig holes in it too. Many of the built-in features of Windows 95 reinforced the aspiration of simulating traversing space. SkiFree and Fuji Golf were included as time-killing games, and the entrancing 3D Maze screensaver also was one of the most bizarre and intriguing default elements of our computer. |

|

I remember spending hours just turning on and watching that screensaver, mandating myself a certain disciplined stillness while it went on weaving methodically through the randomly generated mazes and thinking there was nothing more interesting you could do on a computer. |

|

Gradually, the computer became more of a place for me to be, and more of a place to explore, than the outdoors was. And the amount of time I spent with each, respectively, began to shift. |

|

Some of the games I associate strongly with this period are well-known and well discussed, though often as minor and tangential to the main story of videogame history. Petz has a certain presence for its uncannily convincing AI that still manages to be both lovable and occasionally confusing in the way pet behavior often is. And many of the games that came packaged with the operating system, like Rattler Race and Rodent’s Revenge, were adaptations of arcade-y classics, now available for slacking off in your office environment. (But don't get caught, or you will be sent to the Microsoft Excel crypts...) |

|

But none of this mid-90s nostalgia really gets at what was so appealing to me about these little programs. To begin with they were tucked away in file folders and menus that also felt like a sort of castle with secret trapdoors and hidden dungeons to find. I found the tricks of sorting and searching, messing with a file by changing its extension, and rummaging through the file structure of my CD-ROM games and hidden hard drive folders, and was VERY lucky I did not permanently break anything important. Now, as these features are gradually removed or hidden in newer operating systems, to make them more “user friendly,” I feel like a once-unstoppable safecracker who’s gone deaf in one ear, clumsily fiddling around, well aware of how it used to work but now with nothing to grab onto. They don’t let you do that anymore? |

|

There’s kind of a set of base assumptions which animate games criticism and which I think are a manifestation of medium-insecurity around videogames, the desire to tie it to something historical and more significant than just recreational computer programs. This means that the writing and discussion of videogames tends to inordinately focus on their similarity to types of formalized games that existed before computers. This is why videogames are talked about in terms of rules or systems, their ability to create a perfectly balanced curve of challenge and reward, flow states, and skills or reflexes that can be developed or tested. It connects them to things like board games and sports which already have a fairly established familiarity in culture. |

|

In none of these games did I particularly care about rules, and I especially didn’t care about playing in a way that properly exploited the underlying systems to earn more points or “progress” in a typical way. The slower and less demanding the better. I became an expert at finding ways to infinitely defer having to play these games properly or well in favor of just wandering. |

An example: why trap cats or collect cheese in Rodent’s Revenge when you can just zigzag around the nooks and crannies of the course set to low speed and low difficulty, seeing what strange ways you can arrange the boxes? |

|

Similarly, in Rattler Race, ignore apples, ignore other snakes, ignore ball, pretend you are a snake exploring an interesting box you’ve found yourself in. |

|

Did you know you can walk sideways off the course in SkiFree? Did you know you can even walk back up the slope? It’s slow going, and fairly pointless, but discovering I could do this blew my mind a bit. I hiked amidst rocks and trees, watching the NPCs weave down the slopes, and it was a good way to put off getting devoured by the yeti, which happened if you went too far down the course.  |

|

I loved Encarta MindMaze too, but more for its mysterious denizens and winding floor maps than the trivia challenge it presented. Because the questions were lifted from the Encarta Encyclopedia in what seemed like a semi-automated process, some of the questions were strangely obvious (all the wrong answers were irrelevant) or the answer was even included in the question itself. The point of the game was to progress from room to room, answering multiple-choice questions as you go, and ideally you’d find the quickest path to the stairway to the next floor. I always found it more satisfying to uncover every corridor and dead end on the map before proceeding, though. |

|

This example may be slightly tangential to the overall point of this piece, but I also think it’s compelling: I would also often set a CD-ROM version of the board game Monopoly to play itself with four COM players. As the tiny hat, or iron, or dog, or whatever would go through the machinations of real estate buying and selling the game ostensibly represents, I would come up with little soap opera-like plotlines that these events represented, dramas, betrayals. And it began to have a cyclical tone as they would chase each other around the eternal circuit of the game board. Maybe this is why later, as a game studies researcher, the appeal of let’s plays and watching competitive gameplay or speedruns immediately made sense to me. If I could pick anything to serve as musical accompaniment to this essay, it would be the music the software played while this was all going on. |

|

Another videogame which defined my childhood and that I still talk about all the time is SimCopter. The best thing about SimCopter was that it had cheat codes, which I made use of despotically, to the point that I can’t remember ever playing the game “vanilla,” without a whole stock of free copters and equipment. I’m the CEO of McDonnell Douglas. |

|

SimCopter is, possibly, the first 3D open world game! A format that, by now, has become so typical and codified that I can’t imagine ever desiring to play any of the several AAA offerings in this paradigm that come out every year. But in the late 90s it was the culmination of what I had wanted from the worlds within a computer. The interesting thing about SimCopter is that the city goes on, missions begin and end and chunky sims and cars wander around regardless of what you do, and when you can instantly unlock all of the helicopters and give yourself infinite money, you don’t need to particularly care about the “time pressure” implied by this. Instead it’s more like watching an ant farm. |

I would try to see if I could land on every type of building. I would try to see if I could destroy every type of building. I would get out of my helicopter and walk around, much moreso than the game intended me to use that feature. The sim people would make weird little grunty noises when I walked up to them and then at some point I would get stuck on a chunk of invisible level geometry, my smudge of a helicopter pilot would start vibrating, grunting, and producing a “boing” noise, and I would have to shut the game down and start over. |

|

Only approximately a quarter of the map of a SimCopter level is made up of a city area where missions and events will actively happen. Even now this seems like such an interesting choice to me, to include an excess of ambiguous hills and mountains around every side of the city that most players would never even go to (and if you go beyond the edge of that, you wrap around to the other side of the map… no end!). The icy light blue that demarcated the tallest points of these mountains seemed to glint and promise something mysterious. I would fly out there and feel a weird sense of accomplishment when I landed my helicopter and walked around on the snowy areas, even though I never “found” anything.  |

|

This promise of something ambiguous, inexplicable, mysterious, unpredictable, a promise that doesn’t even have to be fulfilled but just held out as possible, is, I think, the primary draw of videogames for me. |

|

Then, the ultimate space was the Internet. When we got dial-up internet, I quickly found Neopets and had my parents sign and fax(!) in a permission slip to play, a scenario which seems so unimaginably quaint today, I googled “neopets permission form fax” to make sure other people also remembered doing this, and I hadn’t made it up. |

|

Neopets was, of course, presented in a spatial metaphor. Every region was represented by a page and by clicking on different parts of the page you could find games, events, food shops, and so on. It was an element of the “information superhighway” metaphors of the time (and you were likely visiting the site in internet explorer or netscape navigator… you may have found out information about the latest Neopets events by exploring a webring or even set up your own page in a geocities neighborhood). |

|

The animating thrust of what was unique about the Internet was this image of traveling around the world while seated at a desktop computer, and Neopets made this into an enticing fictional world full of cute pets and flash games. Of course it was a runaway success that ate up many of my preteen afternoons. But it was also the first time I was really handed tools to make a space (SimCopter had SCURK, but I didn’t have the patience to figure it out.) |

|

PetPages (a small homepage that you were allowed to edit for each of your Neopets) ended up teaching a massive subculture of preteens more HTML than professional adults may have known at the time. While their stated function was to be a sort of “about me” or journal for your Neopet, many of us would just use them for whatever. PetPages full of game tips or profile themes were very popular, I remember adding art of my OCs and making an abortive attempt at hosting an “original sprite comic” (????) on mine. |

|

Neopets also offered the ability to make simple choose-your-own-adventure type hypertext stories, similar to what Twine offers today. I never did anything too elaborate in these but playing around with them hatched the idea in my mind that I could make game-like things, which I pursued variously over time. |

|

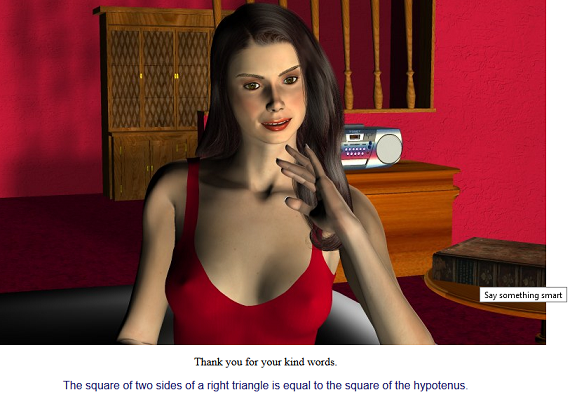

Tangentially, another pre-Twine hypertext story that impressed me was “Date Ariane,” a sort of softcore porn game (ostensibly authored by the main character herself) that has been around in various iterations since 2004. I don’t remember exactly when I encountered it but I definitely lied to my date about being 18 (sorry Ariane) and over several days methodically explicated every pathway with a combination of technological marvel and driven adolescent curiosity about sex. I’m kind of too mortified to write anything more elaborate on this one.  |

|

Beyond this, there were also Neopets forums, which had the vibe alternately of chilling out at someone’s house after school (if it was slow), or trying to talk over a crowd in a rowdy lunchroom (if it was busy). Forums as conceptual “places” to “hang out” similarly defined a lot of my Internet experience through middle and high school. I “hung out” at the Nintendo of America forums, which had a very hands-on mod culture (and I think they were people who actually worked for nintendo) as well as contests and activities like fanart contests and “summer camp,” which I remember being very excited to prepare for but next to nothing about how it actually worked. I developed a passion for obscure, evil anime boys. I tried to show one of the mods a piece of fanart that I made of Bass from the Megaman series but I scanned it at such a high resolution he couldn't make sense of the image when it finally managed to load (it was the first thing I did with this new piece of technology). When I finally got “post of the week,” an honor which permanently doubled your signature image height(!!) I immediately updated my siggy to feature a truly awful oekaki drawing of the atrociously named Llednar Twem that I had labored over for hours. I immediately felt like Big Man on Campus, or whatever. |

|

But, my last year of High School was when Facebook opened to the general public, and for a short window my parents WEREN’T there, so it became the new place to hang out. Now it’s a nightmare combo of professional contacts, people I barely talked to in high school, family members, and old college friends and I can’t think of a single post I would willingly send to all of those audiences at once. Over the next year I also got a Tumblr and Twitter account, I think, and gradually stopped visiting forums altogether. |

|

The internet became a lot less spatial. The “feed” and “frontpage” metaphors of social media and news sites respectively both conceptualize the Internet as not offering a space but a type of document that is unbound by the limits of a sheet of paper. Which, yes, the technology can also do this, but by becoming the dominant forms and gradually shutting down alternatives these approaches have cut down on the imaginative approaches that treated the internet as a “space,” and it’s potential as a place to escape the limitations or ways you didn’t fit in “irl,” to make a persona and hang out in a place where that persona would be accepted, to make places and personas with other people. It also conveniently meant that advertising could take over as insidiously as it had a hold on traditional magazines and newspapers. |

|

Even though it’s quickly faded over the past few years, as discontent with social media and typical approaches to web publishing rises I’ve tried to revive some of the spatial feelings of the internet by building my own HTML-based homepage on Neocities and starting a webring. I’m also still disinterested in most mainstream games and the videogames cited in typical histories of the form. Why do I study and write about them so much then? There’s really nothing like finding a new game that scratches the same part of my brain as SimCopter, MindMaze, Neopets, Dogz, SkiFree etc etc did, that’s all! Here are some of my recommendations:

|