Posted by: Em | OCT-07-2020

The tagline for the recently localized 1997 Love-de-Lic title moon: Remix RPG Adventure says “don't be a hero, feel the love.” Like Chulip, which several members of moon's team would go on to create a few years later, moon's primary mechanic is to strengthen the player character's heart through finding love scattered around the world. In Chulip this takes the form of figuring out the conditions that will allow someone to consent to a kiss, in moon it can take the form of doing someone a favor, solving a quest, inspiring them, rescuing the soul of a dead animal, or even just learning something about them. Both games proceed in a fairly open-ended fashion, with your strengthened heart giving you greater ability to roam further in the game's world and discover new challenges.

While in Chulip this heart strengthening is primarily self-improvement (the girl of your dreams only wants a boy with a very strong heart and a well-practiced kisser), in moon your quest is explicitly contrasted with how The Hero moves through the world. Deliberately set up as a riff on the single-minded player grinding their way through the latest JRPG, to the inhabitants of the game world The Hero appears to wordlessly plow through their towns, rummage through their stuff and kill any animal they come across. This act has scattered and hidden love across the land, and you, a boy who has been sucked into the JRPG's world, have to find it again. There are easy comparisons to be made between moon and Chulip and more recent videogames that replace the standard battles or violence that progress many mainstream games with some sort of non-violent alternative. But for a lot of reasons moon (and Chulip) tend to be more interesting to me than recent approaches to this discussion within games criticism, and not just for their historical interest.

I'm not really interested in arriving at overly utilitarian general principles about “violent” versus “non-violent” games. I think the question of violence versus non-violence plays out in videogame development discourse and games criticism as a sort of shadowboxing, and isn't necessarily a productive angle to default to on games that offer an initially novel mechanic. As I've said before, the immediate framing of Untitled Goose Game as either violent or not violent to me seemed to miss the much more unique aspect of it within indie games, that it was actually funny. To say that violence is the norm in videogames and non-violence is a novel alternative betrays a perspective originating in a very particular context of videogames. Claims for the wholesomeness or moral improvement non-violent games represent become questionable as soon as you consider that the precise reason many non-violent games are implicitly excluded from these discussions are their proximity to or actual unwholesomeness.

I'm talking, of course, about the bad objects of videogames discourse that nevertheless make up the majority of people's engagement with the form; free to play mobile games, adjacent to “low-quality” “shovelware” style releases, predatory monetization models, and gambling, visual novels and their association with sex or otherwise deficient relationship ethics, in addition to having “no gameplay,” the unwholesome association of being “playable with one hand,” but also the variety of popular educational or simulator games that hew too close to the banal, whether they're presenting cars, sports, math homework, everyday occupations, or caring for a pet. Basically, in my experience, “Non-violent” as a specific descriptor for a videogame is not very useful because as used it seems to rely on upholding the other underlying assumptions of the “proper games” press and economy, focused on polished, stylishly packaged product, and then only describes videogames legible from that starting point, minus a specific type of physical violence or a “battle system.”

Part of what preceded moon's reputation in the English-speaking world, leading to the level of anticipation around its localization, was its influence on Toby Fox, the creator of Undertale, another RPG that gives you the option to resolve confrontations “without violence,” albeit while still presenting most consequential interactions within a “battle screen.” This made it even less likely for the reception of moon to evade the violence/non-violence framing since this binary is essentially how Undertale evaluates your gameplay choices and serves you a particular ending. What's interesting, and different, about moon is not just that the game can be progressed without violence in a very particular sense, but that it also presents its own deeply-felt metaphysics of love, and on top of such lofty claims, makes a genuine argument for the value of itself as a videogame, while not resorting to claims about the special efficacy of videogames in general.

These are both complex and exciting things for a work in any medium to pull off! So let's start by talking about love.

Love is always on the mind of the inhabitants of moon's game world. The Moon Queen visits you when you sleep, urging you to find more love and giving you increasingly majestic titles as your collection of love increases. It's the one thing the chatty bird in the town's main square files under “extremely important stuff” when he offers to give you a bit of a tutorial, and he later ponders it at night school. Romance, friendships, parent (or grandparent) and child relationships, and hidden personal passions are the animating forces of almost every character's routine and plot line. It's even speculated that the world itself is made of love. This is the context the single-minded JRPG Hero arrives into, stomping past NPCs and slashing any creature he sees. Shortly after the player character arrives in moon world, you witness the hero attacking a humble slime and leaving its corpse (still rendered charmingly in claymation) on the forest path between your Gramby's house and the town.

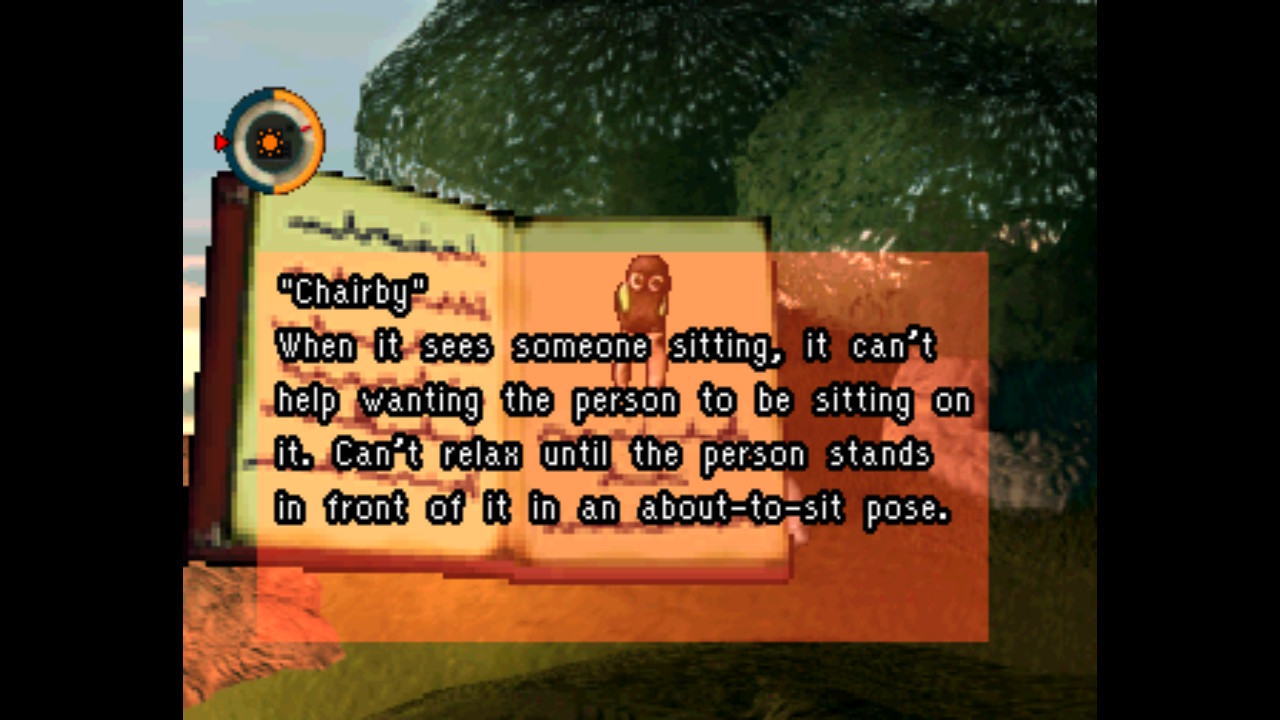

Once you gain the ability to see them, it's kind of shocking how many dead animals litter the town, the banal ubiquity of harm in the world. Bodies sit on the shelf in a shop, in the middle of a well-trod path, next to the fountain in the center of town. Their souls are restless too, zooming around, lingering out of reach, or only emerging under strange and specific circumstances. The search for love in this game, either from animals or the non-animal NPCs, (and the lines can be, deliberately, I think, blurry; a society of NPCs worships an “animal” as their god, for example, while many of the “animals” are more humanoid than some NPCs), rewards attention, patience, and revisiting familiar areas many times. Like in Chulip, there's often a voyeuristic component to how the game encourages you to play. Starting with careful observation, rather than selecting a specific correct action, is seen as key to understanding. While characters in moon world acknowledge you if you try to talk to them, for the most part they don't seem to mind or even sense the “invisible boy” following them like a shadow.

Your first bits of love come from things like running an errand for your Gramby, and catching the aimlessly hopping soul of a tiny slime monster, but gathering love quickly becomes increasingly complicated. It's partially a symptom of another era of game design, but many of the ways to gather love seem vague, incomprehensible or even counter-intuitive. Part of this is also by conscious design, though, and can't just be dismissed as conforming to the orthodoxy of the day. While a lot of the games' puzzles require very specific connections which you may not pick up on, (or, indeed, the provided hints may send you in a completely wrong direction), and the only in-game option for seeking help is also frequently obtuse, this seems a deliberate acknowledgement that while love is fundamental, it's also often mysterious.

Why, despite rhapsodising about love and using primarily non-violent mechanics, do Chulip and moon feel so different to me from the sort of consolidated call for non-violent, wholesome, comfy games, which is largely kind of uninspiring to me? I think the complexity of forms love can take in these worlds is what is so compelling about them. moon and Chulip are non-violent in some sense (though there are several instances where your character gets into a scuffle or has to initiate some slapstick antics on themselves or another character), but it's hard to argue they're wholesome. Over the course of moon, the invisible boy has to consume psychoactive mushrooms in a cave, purchase chloroform, light himself on fire, sneak into an old man's house to look through his drawers, dupe the King into parting with one of the most expensive items in the game, the list goes on. And this is not even to mention the subtextual voyeurism of following around characters until they reveal some secret or you “see” a particular side of them. What I'm saying here is not that moon is secretly dark or twisted, but that it allows for a level of strangeness and perverseness, in the characters, in their secrets, in how they want to be recognized.

In some cases this makes characters a lot less initially loveable, and a lot more weird. Despite this, I think it's meaningful that within a videogame, a medium tied up in curative or at least deterministic idealizations of what it “does,” moon often ends up arguing that love consists of meeting people where they are, as strange as that may be (like the guy who finds his happiness digging a hole in a haunted house basement, or the baker isolated by his bizarre secret).

A good example of what I mean by this is the NPC who runs a small MoonDisc shop in a cave, selling items which you can play on the in-game music player (most areas in the game have no particular background music, but just play atmospheric noise). If you talk to him, he'll condescendingly test your music knowledge, commenting that you probably don't know most of the songs he does. Instead of, I dunno, some contrived plot to teach him a lesson about not judging others, this character's love is collected by indulging his eccentric interest, eventually passing his quiz and leading him to admit that maybe you are friends. What is initially standoffishness or elitism transforms into the way he shows the particular type of love that an omnivorous taste for the musically strange and obscure contains. This is a love that the game's ambitious soundtrack also demonstrates, featuring over 30 musicians, almost every one from a totally different genre, including an anthropological recording of a performance by indigenous South American people, described as a transmission from earth itself.

Love is not a natural state that one can disrupt or a state of perfect harmony they can correctly integrate themselves with or bring about. Even a utopia of love, where violence and exploitation are not even options, is effortful, even difficult. In moon's metaphysics of love, it is literally something that has to be practised to gradually facilitate your movement through the world. But this difficult love also allows a representation of love in all of its strangeness. It's the comparative emotional ease of a lot of non-violent or wholesome games that doesn't really work for me, games where the right choices are distinct or there's no wrong choices at all, settings where you integrate yourself into or bring about a perfect harmony, worlds where love can never truly touch or surprise in its specificity and strangeness.

That's not to say that moon's vision of love is perfect; this thread by @webbedspace offers a comprehensive overview of representational issues and content warnings for the game, including a more complicated take on the anthropological recording mentioned above. He points out that many of these issues feel like a consequence of a very 1990s vision of multicultural harmony that doesn't account for historical disadvantage and harms, especially towards indigenous societies via imperialism. This is a sense in which moon's depiction of love dates itself, and is very limited. However, the elements of its depiction that I think are most touching and meaningful are the ones that depict coming to peace with love as a friction or as a challenge. This is less of an immediate “feel good” outcome, and it is ridiculously frustrating to get stuck. But it creates a world where the practice of love still feels real and consequential, even within the knowing fakery inherent to a videogame.

(From here on I will discuss the late game of moon, fully spoiling the ending sequence. If you're reading this piece because you're on the fence about playing the game and still want to be surprised by the ending, stop reading here with my endorsement that I think the ending was very good.)

The bulk of moon's gameplay consists of gradually increasing your capability through practising love, both to the souls of the killed animals and the more human characters you encounter, and being able to more fully explore moon's world. As you explore, several characters give you a cryptic exhortation to “open the door,” and you find mysterious ROM-chip like tablets that appear to reveal underlying secrets of the world. As you connect with the people spread throughout moon's world, you also gather some seemingly-random items that can be repurposed into spaceship parts. Boarding the spaceship takes you to moon world's moon, where Dolottle and the Moon Queen live along with all of the animals whose souls you rescued. On the moon is a door surrounded by more ROM chips, which describe the personalities of the game's NPCs, and the Moon Queen's palace. When you enter the palace to speak to her, she implies a vague awareness of the predetermined nature of the world, but seems to hope that the player character, using the love accrued in the game, will be able to open the mysterious door on the moon, potentially changing the fate of the world.

The core argument of these games-about-the-nature-of-videogames-games can often be quite cynical about their own existence; that the player shouldn't have initiated playing the videogame in the first place which led to this inevitable conclusion. It expresses a degree of awareness of the general bullshit of the format, but doesn't engage with these contradictions too deeply and instead seems to agree with the forms of disapproval ranging from moral panics to indifferent dismissal that playing videogames is either a pointless or actively unwholesome pursuit. Even though this “meta” turn is marginally stylistically innovative (though has gained stylistic tropes in its own right), it doesn't really propose anything about what videogames should do or can be; instead they seem to only really endorse throwing up one's hands and giving up. This is a conclusion that moon fortunately avoids, and which makes its entire project matter beyond its internal narrative.

Still, it was the path I was fearing moon was going down, as the player character failed to open the door on the moon and The Hero appeared as a surprise stowaway on the spaceship, slashing through all the rescued animals again, effectively undoing all you'd done during the game over the course of a few seconds. The Hero attacks the Moon Queen, then the invisible boy, and, having slain every creature in moon world, the animate suit of armor clatters to the ground. Then, just as at the start of moon, before the boy was pulled behind the scenes of the game's world, you hear your mom's voice telling you to turn off that videogame and go to bed. You're faced with a typical sight for the moment of defeat in a videogame: “Continue? YES/NO.”

If you let your cursor hover over the “no” for a moment, you see the boy get up and walk towards the door in the far corner of the room. It goes against your experiences of videogames... to hit “no” usually means to forfeit your progress and give up, right? But this echo of the exhortation to “open the door” in the game implies something interesting might happen. While choosing “yes” to continue sucks you back into the TV to start from your last save point again, walking out the door is the true ending that triggers the credits roll. Alongside the credits, the clay models of animals and the characters of moon world appear in photographs of everyday, actual locations.

moon admits that videogames are fixed, that there's no way to “change the fate” of the game world unless it was already written in a way that allows the player to do that. This self-awareness is evident in the tablets you find, which reveal the secrets to many of the game's puzzles and hidden areas, as well as the ritual that will always cause The Hero to emerge, that take the appearance of ROM chips. Far from experiences of true freedom or empathy, videogames are static and often offer an abstracted and quantified relationship to actions that are weighty elsewhere. We focus on the violence side of this equation, but isn't it equally true that it's much easier to be merciful when it's presented as an explicit goal, rather than trying to puzzle out the moments where it matters the rest of the time?

moon's ending doesn't challenge this, but it also doesn't throw this limitation of videogame structure at the feet of the player, making them feeling uncomfortable or guilty as if they personally initiated what is programmed in advance. Nor does it present the act of playing videogames as compromised or pointless because of this quality of their form. moon's ending makes the case for videogames as affective experiences that matter when we take them with us into the world; being seen in the world and the boy's experiences is what frees the animals and NPCs of moon world from their programmed fate in the game, and enlivens the boy's life.

While videogames may be crude digital representations that struggle to capture the nuances of pain, violence, love, friendship, giving care or aid, the moments of connection through the inherent unknowability of others, isn't this the problem all art has to struggle with anyways? These strange representations, their quirks, their wilfulness, and even their occasional incomprehensibility are also coming from another human. A videogame can't teach you to kill and can't teach you to care. But it can give you something to take with you. From 1997, this seems like a remarkably confident statement for the artistry and value of videogames that many are still catching up to.

Further Reading: