This post is a transcript of a talk I gave at The Practices and Politics of Inclusivity in Games, a symposium at the University of Leicester, a gathering specifically to present research on how to make videogames a more broadly inclusive medium and industry. While there are many present practical issues, I naturally turned my mind more towards a theoretical and historical angle. Is the way that we tell (and repeat) the history of games part of the problems we currently face? Of course. Anyways, enjoy! I also included some recent articles I read after writing this talk at the end that are excellent further reading.

Hi, I’m Em Reed. I’m currently working on my PhD at Abertay University, where I’m researching a history of exhibitions of videogames and other forms of interactive software in art museums and galleries. This research hopes to support what is an often surprisingly vulnerable part of our cultural history. Videogames are still new to many cultural and art institutions, and simultaneously, because of their ephemeral nature as software and institutional bias against so-called disposable entertainment, they are also at risk of simply vanishing or becoming inaccessible.

By investigating the collection and display practices of museums and examining the arguments they present for why games are a worthwhile and relevant part of culture and the arts, I hope to draw attention to common arguments and their inadequacies, as well as work ways of expanding viewpoints on what games are and what role they play in our culture in my own curatorial practice. But what does this have to do with inclusivity?

Museums and galleries tell the story of our culture, and the practice of exhibition creation is really about telling a story using the medium of space and objects. Each retelling of a story is an opportunity to rebuild our knowledge of things, the history we tell ourselves and incorporate into our personal identity as members of that culture. Overall, I want my work to interrogate where we are in creating a history of videogames through collection and exhibition, and in what ways this history can be made more comprehensive and representative of a wide variety of practices.

This is difficult for many reasons. The general public perception of videogames as a shallow commercial entertainment product leads to an environment where only hobbyists and enthusiasts are concerned with their long term preservation. This situation is even facilitated by the industry itself, which James Newman notes, has a “forward looking” orientation, where the best game is the one that hasn’t been made yet and consoles are rapidly obsolesced and replaced by often purely cosmetic advances in graphics and technology. Mainstream game companies rarely show any concern with preserving development materials, history, and even copies of the games they make, which has the effect of leaving some of the most thorough and effective methods of game preservation and access, like emulation, in legal gray areas. It also means that games that produce long-term, commercially successful IP opportunities are much more likely to be protected by the companies who currently keep track of this material, while games that don’t tick these boxes, or even once famous IP that fall out of esteem begin to slip through the cracks.

When the history of videogames is told, whether it be through books, exhibitions, or pop culture nostalgia, it is often a consumer history. That is, the focus is on a lineage of generally commercially successful consoles working towards the endpoint of the modern generation of consoles, and the influence of long-standing IP, usually ones with current-gen sequels which the gallery visitor can, presumably, leave the museum and go buy. With game companies cooperating and providing support for many of these exhibitions, it’s hard to ignore the fact that a profit motive exists behind this the institutional legitimization of their products. However, there is also a sizeable chunk of gaming history that exists outside of current commercial profits. If the current profit potential of a property or company is what partially motivates its inclusion, are these exhibitions really dealing in history at all?

Homebrew culture, experimental peripherals, the games of the net.art movement and beyond, Newgrounds, the CD-ROM boom of the 90s. These are just some of the things that are almost entirely forgotten by a history of games that begins with pong and ends with the Xbox One. What these marginal practices have in common is that they in some way intersect with messier and more complicated elements of broader culture, like the exclusivity and impenetrability of the contemporary art world, like piracy, or education, or the management of the body, expressive or feminine topics, vulgarity, and so on.

Perhaps an illusion of a self-contained history of games based on a supposedly universal experience of nostalgia– which favors specific cultural, gender, and age demographics I probably don’t have to name—is more palatable at first glance but it’s destined to be a limited and inaccurate history. It’s this sort of thing that says, for example, that women need to be ‘let in’ to game development when they’ve been there all along, or that indie or artgames are a 21st century invention, and these can be well-meaning misunderstandings that completely erase some of the most innovative and interesting work done in digital games.

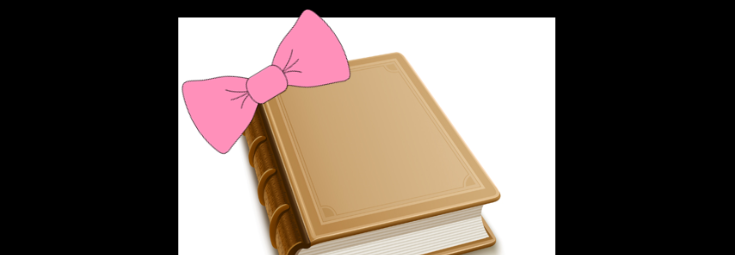

Unfortunately, many recent exhibitions of videogames in museums do little to dispel these biases. Game Masters, for example, is overwhelmingly male, with only one of the designers cited by name being a woman, Paulina Bozek who worked on Singstar 2, and the separate ‘Indie’ section is heavily weighted to games that have come out in the last decade, with only two creators featured whose work is from the 90s or earlier. Put simply, this is a very poor attempt, in my opinion, at the described aim of “highlighting the key designers who have had a large influence on videogames and videogame culture.” If this is a canon the current perspective on what makes games “relevant” or “influential” produces, is it really a perspective worth keeping? I don’t think so.

Museums and galleries staging major shows of videogames tend to not take many curatorial risks outside of this rapidly emerging canon. Besides a few interesting picks, such as Dwarf Fortress, MoMA’s collection of videogames mostly overlaps with developers and titles featured in Game Masters, with around half of the titles found in both collections, and the Smithsonian American Art museum outsourced a portion of their curatorial work, handing over a sizeable chunk of the selection process to an online poll. Coming to the present, in 2016, described as the first monographic show of a game developer, The Game Worlds of Jason Rohrer at the Davis Museum made the bold choice to exhibit the work of someone whose work is already owned by the MoMA.

Clearly people who say videogames are a young medium still finding its feet are being left behind, as museums, through their collection and exhibition practices, are already building, and then repeating and strengthening a canon through it’s replication, not just in one institution or touring exhibition but between them. When I started my research into this area I thought I would see the beginning of the formation of a canon. Maybe it is something that happens very quickly, especially due to the digital and reproducible nature of computer games, but these exhibitions coming from different institutions and continents still have a notable degree of overlap. The rhetoric of a canon is already here, ready or not.

I worry that if we are only concerned bringing women into the industry to bring it closer to gender parity, and then consider the job done, we miss several important nuances. First of all, the important intersections of race, nationality and class that also influences who is able to participate, and whose accomplishments are recognized. Second, the phrasing that we are ‘bringing women in’ as of now, overshadows and minimizes the achievements of the women who have been there, contributing to their erasure from history. This historical situation can lead to women in videogames still feeling alienated from the discipline because they have no historical predecessors, no ‘old masters’ to look to in the way men presently do. Third, without critically investigating what makes it into the canon and what doesn’t, institutions will continue to only be primarily interested in works that replicate the gameplay aesthetics and values already present in canonized works. Work which, among other things, are primarily made by men, and primarily in a commercial context.

Feminist art history was not only about supporting and showing the work of living female artists, but serious research into the past, recovering overlooked artists, subjects, and mediums and deconstructing the logic and rhetorics of the time that had devalued that work. There is, for example, the prime example of women designers and artists at the Bauhaus being limited to working in the ‘craft’ medium of textile. Of course, these women went on to produce technologically innovative, avant-garde, and commercially successful textile work, but it is still painting, graphic design, and architecture, more typically masculine forms which most women entering the Bauhaus did not have access to work with, that the movement is primarily remembered for.

There are many examples, this is just a fairly recent one. This approach to history can be challenging and problematic, because many of the subjects will be decades, if not hundreds of years dead, less documented in public record than their male peers, and from a different culture that the politics of modern gender studies cannot easily mesh with. Similar problems can be seen with our lack of cultural memory about women in videogames in the present canon. However, we are lucky that these events are not so far behind us, and many women who participated in gaming history are still alive, or have associates who can attest to their memory. It’s a precious resource feminist art historians didn’t have when trying to understand figures like Artemesia Gentileschi and Maria Sybilla Marian.

One notable example in games is the work of Theresa Duncan, which was recently restored in 2014 by the arts organization Rhizome in New York. While her unfortunate passing cut short a career of written, film, animated and interactive works, the three CD-ROM games Duncan designed during the 90s were critical and commercial successes, and also unlike anything that had existed up until that point. They were interactive stories for girls, unique enough already in the landscape of computer games, but they also took on a ‘hand made, folk art’ visual aesthetic, soundtracked by grungy punk, combining topics dark and mischievous with the more typical whimsical fare offered to young girls. When I played the restored titles, I was transported back to other educational software from my youth that had left such an impression on me. Where were they in this history? Who made them?

Critic Jenn Frank noted in 2012 that Theresa Duncan’s games, though successful and highly praised, had been almost totally forgotten. In fact, she says that the internet, flooded with obituaries and the circumstances surrounding Duncan’s death, became an unkind documentarian, slowly turning Chop Suey, Smarty and Zero-Zero from “has-been” into “never-was.” In many ways, research into videogames relies on the safety net the internet offers, providing the structures for communities to collaborate on the emulation and documentation of favorite games from the past. The internet can also, through a single missed link in the chain between content, service provider, internet provider, search engine and so on, obliterate or obscure the history that’s there, making this complacency a dangerous trap. Rhizome made the games known and playable once more in 2014 through a cloud emulation service, and since then the games have also been exhibited in the Dundee Contemporary Arts centre in Scotland. The exhibition opening was held concurrently with the international Digital Games Research Association conference, and it was intriguing to me for how many scholars her work was a revelation.

Also at that conference, on a panel about the discourse within game studies, someone suggested that the infamously combative undercurrent of the young discipline of Game Studies may be a side effect of all of us being ‘gamers’ ourselves, and therefore, inherently more interested in competition. As an avid gamer, but only in the sense that I’ve maintained my Animal Crossing: New Leaf town for over three years running, I cringed at the huge amount of games, but also my own aesthetic appreciation of games this implication excluded. So where does a game with no competition, no points, no goals, like Theresa Duncan’s work, fit into that person’s imagined discipline? Digital games offer so many possibilities besides that, and so we run the risk of just creating a Ms. Game History by simply supporting female creators without reconsidering evaluative ideologies and forgotten practices that determine our games canon.

With my own research, I am both investigating the history of exhibitions of videogames and software in art museums and galleries, using the work of play theorist Brian Sutton-Smith to examine the arguments made about the value of these playful objects and activities, and then stretching my own curatorial practice to present the history and present state of digital games in new ways. While I don’t work from an explicitly feminist lens, including the overlooked and marginalized perspectives and practices in games history is an important priority to me, because I think a neat and tidy consumer history that many exhibitions and books on the subject present is simply inaccurate.

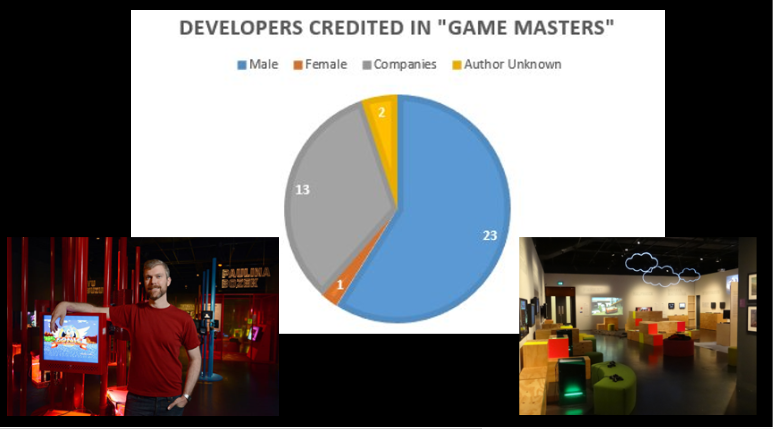

My first project was consultation on the exhibition PLAYER held at the Perth Art Museum in July through September of this year. With this exhibition my supervisor and I attempted to shift the narrative more towards examining the relationship between player and controller, rather than focusing on ‘auteur’ developers or ‘iconic’ titles. We also included several interesting developmental dead-ends, like a custom Doom controller for the Jaguar that seems impractical and awkward by today’s standards. The final section also gave us a bit of freedom to feature experimental contemporary work, such as Line Wobbler, an instantly accessible “one dimensional dungeon crawler” that’s controlled by tweaking a spring.

I also co-curated the 2016 Blank Arcade exhibition to accompany this year’s international DIGRA conference held in Dundee, which runs until the end of October in the Hannah Maclure Centre. The Blank Arcade is an annual show that conceptually fills in the blanks left in mainstream games and digital interaction. We received 57 submissions from all around the world and I was really happy to be able to feature games like You Must Be 18 or Older to Enter, by the development team Seemingly Pointless, a game about navigating porn sites as a curious kid in the late 90s that lets the player ponder feelings of curiosity, embarrassment and anxiety in a humorous way. We also featured eBee, a e-textile boardgame by the collective Pins & Needles, that brings the forgotten connections between textiles, quilting, computing and technology to the surface. Beeswing is another interesting one that deals with issues of aging and mental health in a rural Scottish village, it has an acoustic score and really amazing handmade graphics.

Looking forward, I’m interested in doing more research on histories of game design tools, and the communities around them. This would hopefully highlight creators and practices that don’t receive as much attention in our current game history timeline, and broaden not only what we include within the history of digital games, but also what the public sees digital games as capable of.

Further Reading: