Posted by: Em | MAR-20-2017

Anna Biller’s The Love Witch (2016) by it’s very nature initially confounds attempts at reading it for meaning because of the alternating layers of parody and sincerity, skilful periodization and deliberate anachronism that make it what it is. Meticulously shot as an homage to bold, colorful and psychedelic horror flicks of the 70s, the trailer can usually fool people into thinking it may be a film of that time, or at least give them a second of pause. And while watching the film itself there’s still moments that feel lifted from the time: a corny “You’re over the line!” BIFF! “No, you’re over the line!” in the sheriffs’ office, the gaudy occult decor and bubbling pots in Elaine’s apartment, but there’s also moments when it deliberately breaks down.

“It’s like you’ve been brainwashed by the patriarchy!” Elaine’s SUV-driving, married but childless, modern-woman friend Trish says while they’re sharing tea and cake in a frilly, “women’s only” tearoom. But of course, Trish is not as glamorous and daring as Elaine, so what does she know about Love Magic and Sex Magic?

Elaine uses magic on men to get them to have sex with her, and then, through this process, tries to draw love out of them. Throughout the film it always goes wrong. All of the men she seduces die. I encountered some readings of the film, that argue because of its glamorous and very deliberate settings, costuming, and makeup, it is simply a long and glossy promotion for the liberal/choice/sex posi faulty feminist idea that femininity, glamor, (and giving it to men through sex,) is a source of power. This is a fair critique of a hell of a lot of “feminist” media and I think it’s a good sign that people now have a baseline suspicion of these things because when we didn’t we ended up with like, Buffy Studies or whatever.

But I think it also presumes that Elaine is coming across as empowered. Throughout the film she’s far from a victorious heroine sticking it to weak men. While her actions are obviously underhanded, she does make a fair point in defending herself against the charge of murder, her intent was never to kill any of the men who wind up dead from the power of her love magic. She screws up repeatedly, and never quite gets what she wants (until the end, arguably.)

Magic in the film is obviously a metaphor for something about how love and sex works in the modern world, but what exactly? My immediate takeaway was that it was depicting those forms of capitalist-heteropatriarchy infested false feminisms even more literally as a cult than they already are. Elaine eagerly takes to witchcraft because it’s something that affirms she has some worth, feedback she had initially only gotten or had withheld from her by certain men in her life, like her ex-husband Jerry or her father. On her own, and when dealing with other women “in the know” she’s happier with herself, feels part of a community and has more confidence. But often the tone of the larger witchcraft rituals and meetings is distinctly uncomfortable.

This comes mainly from the presence of Gahan, a creepy warlock who oversees all of the local rituals. Under the guise of liberating the powers of love and sex magic, he gropes and oogles the women at the meetings, forces them to “ritually” kiss him and engages in inappropriately direct conversations about their sex lives out of nowhere. He is essentially a grotesque version of the “woke bae,” made clearly ugly so we can see how gross he really is, no matter how much of a hip young thing he may be in other contexts.

There’s a scene about halfway through the film that reveals how Gahan’s vision of love and sex magic works, but also how oppressive and limiting it covertly is. While watching a woman dancing and using sex magic to attract the attention of many male customers at a bar, Gahan, Elaine and Barbara, another witch, have a conversation about the history of witchcraft and it’s purposes, but the conversation is largely driven and shaped by Gahan’s input. This is ironic, as he basically mansplains how the repression of witchcraft is a way of controlling women’s (specifically, of course) erotic energy, which frightened men.

Women reclaiming this power is liberating, as long as they wield it in the right and responsible way that makes men comfortable and attracted to them. In fact, the responsibility for regulating sex and love energies falls to women, because men are just naturally different, (and arguably weaker, right ladies?) Essentially, Gahan has appropriated what could be a tool for women’s self realization, and made it about heterosexual sex and love, the same thing women have long been told to prioritize pouring their emotional energy into, while men still enjoy limited responsibility. This is the feminism that sells makeup and copies of Cosmo, the feminism that says taking your husband’s name is your choice, the feminism that still places the onus on women providing care by framing it as a “special quality” rather than a God-given duty but ends up having the same function of leaving us all burnt out and dissatisfied.

Elaine flooding the men with sex magic that she then turns to love magic in the hopes of finding someone who will give her affection, care, feelings of value etc, always spectacularly backfires. Her first target is Wayne, a libertine literature professor who says he “loves women.” After she seduces him, and the spell is complete, Wayne undergoes a change from the confident free love intellectual he presented himself as. He starts sobbing for Elaine as soon as she leaves the room, and goes on tearful rants about how tough his life is, about how he’s never had love quite like this, and of course, how all the pretty girls are so stupid but the intelligent ones “are so homely and just don’t arouse me.” Elaine nods and listens to poor Wayne but eventually sneaks out to sleep on the couch, and he calls for her all night before dying of a heart attack.

This was the part that got the biggest laugh in the theater, I think because it’s the most true. I feel like everyone in my general age group (mid to late twenties) has dated an awful guy like this who essentially drains you emotionally then accuses you of doing the same (often using the language of emotional labor) as soon as you want to talk about your bad day. Men are happy to take advantage of free love and discourse on deconstructing gendered stereotypes about emotion and expressiveness so long as they don’t have to be the ones caring about a sob story, putting in the emotional effort of nodding and sighing at the right parts because emotional labor is still women’s work. Elaine never receives reciprocation for her care when the men she seduces “start acting like women,” and later, she indignantly realizes that no one was ever there for her when she was alone and crying. By now, she is confronting the sheriff, Griff, who has become suspicious of her despite also going on a few dates with her.

“I take what I need from men, and not the other way around,” she says at this point. But has she, really? Perhaps according to a liberal, sex positive misapprehension of feminism, yes. She was able to seduce any man she laid her eyes on, but beyond that, she ended up giving much more to the men than they gave to her.

When she wakes up on the couch the morning after sleeping with Wayne then hastily retreating from his boring angst, we see Elaine with smudged makeup, in a bit of a daze, lacking her long, dark hair extensions. Vulnerable. Not natural in the way that Gahan would argue women are “naturally” sexual goddesses who have that element of themselves “repressed” by those who fear witchcraft, but natural in the sense that the artifice of femininity becomes obvious. Of course she fixes her hair and makeup before cavorting around outside in the nude to pick flowers and dig a grave for poor Wayne.

We see Elaine without artifice but no man ever does. No man is willing to give her that degree of intimacy, and instead sex is confused for intimacy, acceptance, self-realization, an inherently positive thing. She may, inadvertently, take these men’s lives from them but maybe it’s because, based on what she needs, maybe they had nothing else of real value to give.

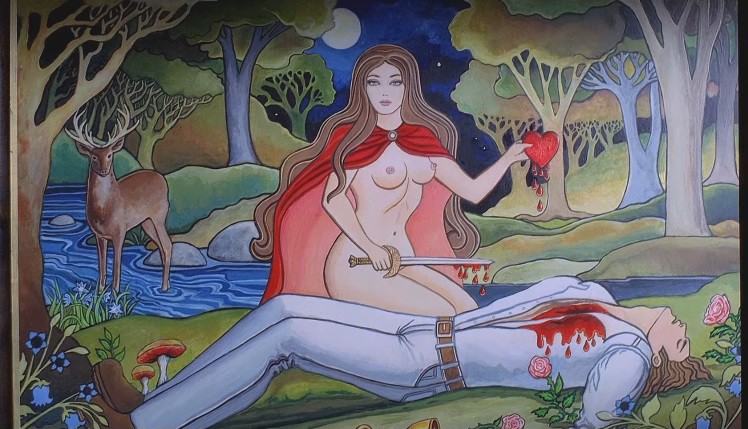

Griff is the one man who Elaine’s sex magic won’t work on. Despite all the ways she tries to charm him, he still maintains his suspicions of her. When she realizes this, she stabs him in the chest, killing him and mirroring an occult painting she created and hung in her room, a sort of conceptual self-image of what she truly wanted. She smiles and imagines a scene of her and Griff riding off on a white horse together. Destroying the reality (and perhaps also your faith in it) of how relationships with men turn out is the only way to maintain the fantasy of Prince Charming for a woman who refuses to compromise on a fantasy of equitable love that is impossible within current gendered dynamics.

There’s a strip in the 4-koma manga Azumanga Daioh where Yukari and Kurosawa, two schoolteachers implied to be perpetually single women in their 30s, discuss the fantasy of prince charming while relaxing at the beach. Given the hypothetical possibility such a prince really did exist, Yukari flatly responds she’d just kill him. The structure of the joke always struck me as similar to the structure of the Zen koan, “if you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him.” Vastly simplified, the koan is a warning both against false teachers as well as letting oneself fall into false complacency. Thinking you’ve met the Buddha on the road to enlightenment only means you’re not there yet. If it seems like an easy answer, it’s not.

In both cases, female characters resort to killing when presented with the perfect Prince Charming, because this ideal source of happiness will always fall through, never satisfy women or offer them equal treatment so long as gender relations remain as they are. No matter how handsome, how kind, how brave, or how dashing your prince, he cannot make the relationship take place outside of dominant patriarchy. It likely will not be sweeter than solitude. Rather than empowerment fantasy, The Love Witch presents the vision of love and sex magic that Elaine bought into as a dead end, but perhaps wraps up with the realization of this. She seemed a a lot happier when she was painting, after all.