Posted by: Em | SEP-01-2017

“[I]t is always the adoration of the past that triumphs over lamentations for the present…” but what does a deep dissatisfaction with how we adore the past mean? A desire for a different way of viewing the present?

I saw Atari: Game Over recently and really didn’t like it. That’s not to say that the idea of excavating the near past is frivolous to me or that the implications of a game cartridge as an archaeological object aren’t interesting but more that this is hardly what the film is about. Instead it’s mostly about how ‘epic’ it will be to recover ET detritus with big digging equipment and throw an overlooked genius of programming back into his rightful spotlight.

Laura J. Murray’s review of Rip: A Remix Manifesto was fresh in my mind as I watched it which I guess you could say made me sensitive to how filmmaking can caress the tepid and predictable interests of some dudes into romanticized male geniuses and outlaws if this film wasn’t even more clumsy and obvious about it. The trod upon fanboys will once again have their day of… publicly enjoying mainstream games and film references? Like the examples cited in Murray’s review of Rip, the only women present are the ones that just don’t get it, the wives, the girlfriends, oh and I guess a chick made River Raid (but Centipede appears in a montage of arcade cabinets made by the great guys at Atari, because of course.)

If chiptune and dad rock is the audio leitmotif of the film’s aesthetic, it’s defined visually by a sort of nostalgic spew that splatters out to cover other things, more than it draws on the actual visual history of games. The funk of the “two things” t-shirt is all over some especially nonsensical animated portions of the film and usually takes the form of turning everything into a vague understanding of “pixel art” that has become shorthand for letting the real gamers in the audience know you are speaking to them. It’s an in joke that everyone’s in on, a bit, I guess, because it’s not really pointing to any authentic past experience.

More broadly, the way pixel art is often deployed to this end rarely makes any sense as history, the ostensible topic of the documentary, but only within “retro.” The simple sprites that made up the games discussed in the film, depicted in sharp, geometric rectangles, were often gridded out in pencil on graph paper, and designed for the hazy glow of a CRT. Early gaming magazines used a clumsy setup to photograph their TV sets if they needed to include an image of the gameplay, far from the ease with which we can generate a pixel-perfect screencap on almost any device now. When being able to flick on “scan lines” in a options menu becomes a suitable way to address these material realities, the way people actually designed and saw these games slips away.

You can buy a luxe coffee table book of sharp, squared-off “pixel art” presented as if these things could never have been seen any differently. This kind of nostalgia changes the past, because of course all nostalgia does, but what it seems to do best is transform the visual elements of these games into static, clean, recognizable icons, not unlike a logo, and the field where both spurious and canonical pixel art is presented becomes a parade of these branded markings, the ideal of infinite scrolling super Mario clouds on perfect Mushroom Kingdom blue. It’s no surprise that many indie and art games use an exaggerated low res or pixel style to enter this lineage of implied purity, simplicity, authenticity. As a visual style it is also “easier” in certain ways, suited to smaller teams and requiring less computing power but these strong connotations of easily fitting into how the history of games now tells itself (mashup art combining pixelated sprites of characters from many different series has always been popular, see the lost art of the sprite comic) is also undoubtedly a big draw that informs seemingly unconscious, intuitive or practical aesthetic choices.

But this is not the only visual language of game history, nor is it necessarily the most immediate or accessible way for independent or artgame creators to make work. This is what interests me and inspires me about things like Flatgames in general and more specifically @ragzouken’s Flatpack which can be used to quickly make flatgames on a device with a touchscreen and a camera, like a phone or tablet. Flatgames tend to focus on traditional media sketches and doodles, often quite unpolished, as their visual sources. Especially if you’re using Flatpack, getting these things in the game space and moving around is probably about as, if not more, fast and easy as drawing a 2 frame animation 8x8 pixel portrait of yourself and making it the player character, and yet while the speed, computing and skill requirements are all fairly low, Flatgames as a guiding concept has resulted in completely different tones, approaches and types of games that pixel art stuff doesn’t tend to touch.

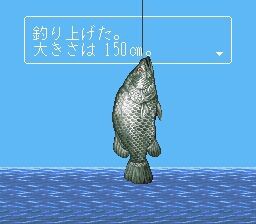

And working in low res didn’t necessitate this sort of minimalist iconic approach that has become synonymous with pixel art, either. Kawa no Nushi Tsuri 2, a Super Famicom fishing game, has dense, patterned chipsets to represent the natural environment that almost have a tapestry-like vibe to them, and jarringly photorealistic fish sprites. Top Banana, an infamous Kusoge for the Amiga again combines photos, cgi, traditional art mediums and pixel art sprites in the foreground over animated parallax backgrounds leading to something that is always swerving into overwhelming indeciperability. These games are just two examples of staunchly non-minimal low res graphics, many of which emerged alongside the first platforms that improved upon predecessor’s graphical capabilities. The SNES was an upgrade of the NES, and to be marketable this had to be immediately visually apparent, the Amiga was also sold as an especially graphically robust option among other home computers. We didn’t always think it had to be like this.

Even beyond moving away from the pixel art monostyle as uniform gamer reference cliche, I think it’s also important, especially in reference to personal histories of videogames as played to move away from representations of nostalgia that rely on re-presenting the visual and audio properties hard-coded into the software. Nostalgia that doesn’t easily fit into terms defined by the companies which have long had a hold on what gaming history survives and how it is presented as we move forward in the form of valuable IP is an overlooked area and also where a lot of marginal experiences are found. If what we think of when we think of gaming nostalgia is a certain monoculture defined by pixel art, certain sounds, certain controllers to certain commercial consoles, all appealing to a lineage of legitimacy and authenticity, then the other side of the coin is maybe weird nostalgia.

For many of the reasons I addressed a lot of people want to move away from nostalgia as a whole, because when it’s deployed through this output-centric framework it not only becomes this series of brands but also equates the experience of nostalgia with a regimented childhood experience, consuming certain genres and platforms in a certain way, and this can serve as gatekeepinng or fanboy test goalposts that many people, like women, like people who didn’t grow up middle class in North America, and so on can’t reach. A lot of the moments in the Atari film that indulged in this fanboyish box checking (and the king of the box checking himself, Ernest Cline, is a major actor in the film’s drama… for some reason.) did feel to me like seeing the punchline, knowing to nod or laugh in recognition, but not really getting the joke. I didn’t relate to why this was important, or rather, I had my own reasons for being interested in the film but the frothing over how great it is to recover ones own lost past in this way didn’t ring true to me, the clueless girlfriend. Yet despite the dominance and monoculture of these popular game histories that are defined by what the imagined default consumer, male, white, middle class, English speaking, bought, despite how tiresome nostalgia circlejerks about the same old shit can get, I don’t think nostalgic thinking is entirely a dead end in productively thinking about videogames.

What I most associate with my memorable experience with videogames, and therefore what I draw on as nostalgic is not really related to visual or musical styles, though the fuzzy orbs that made up Petz characters, jarring sourced sounds and the flat delivery of non-professional voice acting still do tap into that appeal, but it’s much more the sensation of gradually chiseling away at the opacity of computers, the magic wall of color and sound they put up for us that hides how any of it appears on the screen. I was in awe when I read chapters in The Second Self, where Sherry Turkle interviews children at various stages of growing up, trying to understand what level of liveliness and willfulness they attributed to various technological devices. It was seeing the primary feeling I attributed with gaming formally acknowledged for the first time.

The novelty and compelling-ness of videogame experiences for me was not organized around Mario as an icon (in fact, I’ve only spent significant time with the most acclaimed Mario games of my youth through years-later speed-running culture), this is a post-hoc organizing principle. It was much more the feeling of engaging with software, a machine brain, a reactive black box, something that started within a certain realm of real-world analogy (run, jump, collecting money is good) but quickly proved unintelligible or unpredictable by virtue of how the binary digit-al can only be a hollow approximation of the actual even at its most advanced/convincing. I miss the feeling, that may, in fact, be permanently lost, that a game could be truly generative, not in the procgen sense of recombining a set of established possibilities, but in the sense that you can actually be in places that don’t exist convincingly while you’re dreaming.

The opacity of videogames, their modularity, their closed-offedness, their eager, friendly responsiveness, even when they’re hurling hostile projectiles at you, their softwariness. In his book of essays on the weird and the eerie Mark Fisher’s eerie is defined by absence, an eerie sound with no apparent source, but weird things are unavoidably present. He puts it: “ a weird entity or object is so strange that it makes us feel that it should not exist, or at least that it should not exist here. Yet if the entity or object is here, then the categories which we have up until now used to the make sense of the world cannot be valid. The weird thing is not wrong, after all: it is our conceptions that must be inadequate.” I say weird nostalgia because I crave such weird moments as definitive of my history as someone who played videogames, who used software, who continuously had to wrestle with what technology was and wasn’t capable of, what kind of machine brain I was dealing with, and yet having my expectations confounded and having to re-evaluate was a type of pleasure.

This past may be unrecoverably specific, particular to my own specific age and level of access to the software of that time, and how my knowledge developed from that point. The feeling of being perpetually on the edge of mystery may be lost with the technical knowledge of what’s underneath the colorful shell, but then even the guts can have a trickster-like quality to them, and while far less frequent this old feeling will still sneak up on me when I least expect it.