Home > Writing Portfolio > SPEAKING MY TRUTH [real] [NOT clickbait]

Posted by: Em | SEP-10-2018

Maybe it’s because we’re getting older, maybe it’s because we all have no fucking time anymore, but in general both strictly indie-oriented and broader mainstream publications seem to now not only accept but embrace the model of a condensed “quality” videogame experience… Something like Firewatch was I think the best example and the tipping point of this trend. An alternative to the focus on “hours of gameplay” or “replay value,” you can now have a one-and-done moment of immersive gaming spectacle that only lasts about as long as the latest immersive MCU spectacle plus post-credits scene. So theoretically “as a consumer” now I can choose between something which demands my attention for 20/40/60/100+ hours, or one that does for 2–3 hours, theoretically because neither would probably run on my laptop. I guess I can see how this is an important difference if you’re an active participant in the “dadification” of the medium or for other reasons don’t have a lot of time or have to play a large volume of games. To me they don’t seem that different, though.

The existence of a lot of these videogames, of this new attitude towards game-making even, owe a debt to “walking sims” becoming normalized, and even worth a few BAFTAs (largely because they were able to differentiate from the still-reviled/now-associated-with-asset-flip “unity horror games,” this was the context in which the tonal bait-and-switch of Gone Home made sense, by the way) becoming things that medium-size studios make, becoming things that have orchestral soundtracks and celebrity voice actors, becoming the inheritor of the narrative of futurity and technological innovation but this time also conveniently fitting in to your busy lifestyle.

I think the idea of the videogames we buy representing less and less a specific thing we want to enjoy and more and more a “buying in” to a certain type of eventual, aspirational supermedium is pretty astute (see the “New Games” chapter of James Newman’s Best Before) The imaginary of what you’re “buying in” to at least with the more mainstream videogames has also really ossified since probably around the release of the ps3. While “narratologists” like Janet Murray were hyping up a future where every NPC could be an advanced chatbot, and “ludologists” foresaw, I dunno, the platonic ideal eternal mario level that would both teach you how to play itself and manage “flow” perfectly as to never stop being both “challenging” and “fun,” in the end we have to admit we got neither of these things, really and kind of the worst of both worlds. Most of these major AAA releases that are an event of preview posts, review embargos being lifted, and the pinning of hopes of futurity have essentially the same structure, scripted cutscenes or lines of dialogue giving a vague shape to a few mission types spread around an increasingly generous container. This map/world/series of rooms can be extended or constrained to make a game longer or shorter, and maybe there are a few branching dialogue paths that will lead to a slightly different ending or sex scene, but in general, these dreams are gone, and clinging on to them as design orthodoxy has started to feel out of touch.

Videogames within this paradigm, while they can demand either a short time or a long time have kind of a universal relationship to attention which is, they want to immerse you, this kind of technological dream of total, rapt attention and loss of self (but the word reminds me more of the scene in a gangster movie where they keep dunking a toadie’s head in the piranha tank until he gives up the goods). As forcefully as videogames try to conceptually differentiate or elevate themselves away from cinema, this is a very cinematic goal. The cinema creates its own fixed audience, comfy chair, dark room, surround sound, snacks in lap, and of course the massive screen, and these games make similar demands of total attention and postural conformity.

But of course there are different types of attention and also a lot of different types of videogames being made even if the majority of money, online discourse, acclaim, and academic energy seems to be going into games that fit this paradigm. I really like how the writers at JRPGsAreDead.fyi have written about ways JRPGs are specifically framed as a “dead genre” by western game writers. Even if that exact sentiment is not as explicitly stated anymore, JRPG-like games are still treated like an evolutionary “dead end;” that a new Dragon Quest game comes out every year can be framed to be as ridiculous as a species like dodos or giant pandas chugging on. As a form they “lack potential,” or rather, the form does not take advantage of the right kind of potential the medium offers. This happens to a lot of things that become the villain of the week: anything involving RNG too obviously, anything involving premade assets, anything involving microtransactions, too many children liking it, too many old people liking it, too many youtube channels about it, not self-reflexive in the right ways, too many women or LGBT people making sincere visual novels, etc etc etc. And yet…

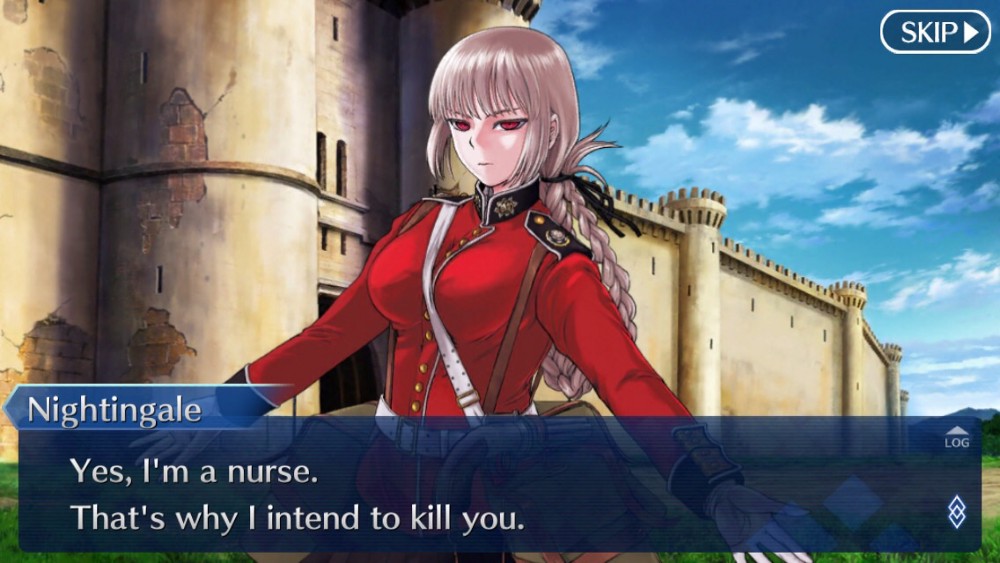

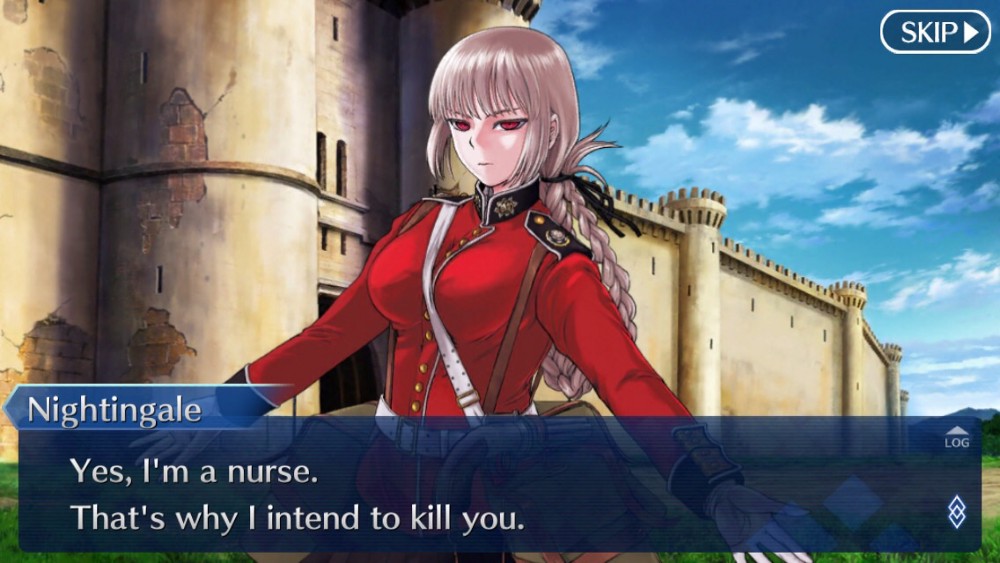

It is at this point that I would like to pause and make a confession. The type of videogame I have far and beyond spent the most time playing this year is not anything with the lofty aspirations of a AAA open world title nor the curated, ultra designed experience of the IIIndie-cinemagame. I’ve been playing a gacha-based phone game, one of the worst, actually (worst rates, worst character designs (&most dubious character premises), worst ingame currency prices, least generous with free rolls, the damning features go on and on)… And a lot of people, even people who are invested in the evaluation of the first types of videogames I discussed, ones about immersive experiences, production value, the future potential of media, are also talking about them… mostly in their off time of course, with a slight tinge of guilt or frivolity… and yet…

To recognize that there might be something to this is not to say that the gacha mechanics are not exploitative and probably just unregulated gambling, nor is it to assert that these games secretly have some design genius to them beyond really knowing what anime character paradigms people like. I feel like to make this argument would be the same as letting what Walking Sims have become off the hook of all destructive logics of the first-person videogame form, just because they take the gun out of your hand, based on an aspirational, future-looking view of what videogames should do versus what they are doing.

When I started my dissertation three years ago, I thought it would be productive to get people to talk about how many games they wrote about they had played pirated, on emulators. I don’t think the arguments from both writers on popular game review sites and academics against the recent takedowns of ROM sites would have come forward as easily or as strongly as they did this time back then. Then I wanted people to talk more about how they came to understand games through reading about them, watching youtube videos, anything besides the omnipresent interaction perspective. Now I feel like we also have to disconnect from the aspirational image of videogames to figure out what they’re really doing. Part of that is looking at the more obvious kind of border work, exploring what we mean by “spam games” or “asset flips” as if this is an objective or natural category of fact, but also looking at what we play which seem like minor or even embarrassing games, and what those experiences are like, how they’re different from the image of gameplay we’re sold. Even moreso than embracing the clean main streets of “casual games,” grannies playing Wii and match three games curing psychological trauma or whatever, minor games without purpose. The videogames that are nothing but byzantine entertainment/money extraction/techno-speculative devices but in the wrong way.

What it’s like to be a person who plays Fate Grand Order:

I open this game at least every day because there’s a minor reward and it only takes about 30 seconds to a minute. Actually, I can be sure of this statement because the game tracks my single login streak, one day less than the total number of logins because I downloaded the game one day, and then started regularly playing it a few days later.

After a screen of news stories and the daily rewards popup you’re on the main menu screen where you can go to the different chapters of the story or the daily quests. Of course I’m greeted by an image of the “servant” (a loosely interpreted historical figure that can be summoned for combat through the gacha screen) who’s first in my party, which is usually my “Tamamo Cat,” the first SR character which I got in the fixed-odds tutorial roll (you always get one SR servant there, but not in any other roll). I’ve maxed her out by now and she’s strong enough to deal with the game’s fairly relaxed difficulty curve. That’s the thing, the main story mode doesn’t offer much resistance in terms of difficulty, especially if you borrow other people’s characters through the support system. It’s not pay-to-win so much as pay for a vanishingly small chance of getting your favorite character.

Based on the main page I can also apparently trade in event currencies for a limited time event I didn’t participate in (I was busy, it looked stupid), look at my own stats, see weekly missions… On days where I only check in, I just pop down to the menu and do the free roll, and maybe a single roll on a limited time gacha if it looked tempting. When I felt like playing a bit more I’d do a chapter or two of the story quests, or now one or two of the dailies, and feed whatever exp cards I’d built up to the character I was working on leveling up at the moment. If a temporary event I wanted to finish was on, I’d play a bit longer, but the general tenor of the game is a sort of accumulation over time that is more numerical than Animal Crossing but about the same pace.

The “actual gameplay” parts are turn-based RPG battles that involve a random draw of cards but also enough strategy so that you can both feel like you can understand the “trick” to a maybe slightly difficult battle if you try again, you can also convince yourself you’ve had a run of bad luck. It’s satisfying when type advantage, power ups and crits all come together to make a huge amount of damage, but not the end of the world if it doesn’t happen. Like VNs, you can play it with one hand, and only half looking at it too.

The more you browse around the menus outside of these battles, the more the game feels like using an OS, selecting icons, paging through documents, organizing and filing and storing things away, and both the maintenance of and poking around in these little nested drawers is a kind of simulation of using a smartphone that exists as a smartphone game. In one screen, you repeatedly prod at static images of your characters to unlock voice-acted lines which you can replay when looking at their character menu. In essence, I think a good analog for what niche these games fill in people’s lives, a niche which in the long run may be not only quantifiably bigger but represent a different kind of commitment/attention/emotional attachment is this piece where Stephen talks about games as an excuse to use the computer and the different type of motivation and attention that implies.

I’ve generally found it more in line with my experiences of videogames to not think of them as a continuation of games in the tradition of wargames, popular games, sport, board games, and so on. Some of these comparisons might be more useful for particular genres, but in general I’ve encountered games as technological novelty first, and then when the novelty wears off something to diffuse or process or somehow get your brain around the imposition of a new technology into life. In this case, the lineage with cinema makes more sense but also a lineage of pinball, slot machines, and other instances of mechanical and automated forms offering the counter (leisure, entertainment, free time) to the work they also increasingly inscribe. When I’m on the bus to a job where I’ll have to check off lists, look at spreadsheets and move files around it is transitory and relaxing to half-pay-attention to a Fate Grand Order mission on my phone. It’s not as straightforward as “gamification” and kind of predates both the promise and critique of the term, stretching back, I think, farther to how technologically mediated entertainments always move in concert with work.

BACK