Posted by: Em | DEC-29-2018

There is a sort of emotional arc to this. I am a writer, also an art historian and curator, as well as someone who is interested in videogames. I’m contemplating the incompatibility of all these aspects of my life, (never mind additional categories like “woman” or “from south-central PA”), contemplating how on reading a piece of personal nonfiction I wrote about being in an art museum, really putting fresh passion on the page as I had never been in one until I was 17, the advisor of my creative writing degree said it made him see art museums differently. Prior he had always considered them to just be a series of rooms full of “1000 pictures of the same baby.” In a hallway full of sculptures of Christs and saints and stained glass windows, glamorous museum staff and bedraggled visitors walk through quickly; this is where exiting through the gift shop has deposited me, at the end of the V&A’s exhibition, VIDEO|GAMES.

Despite being surrounded by 1000 babies, I remind myself that the V&A is not strictly speaking an “art” museum, it’s a “design” museum. But to me, design is one of those things that can only be defined by its simultaneous proximity to and difference from art. This exhibition at the V&A was developed over three years, almost concurrent with the three years I spent on my thesis. I avoided seeing the show until now for my sanity and also for the sake of finishing the thesis, on how videogames have been exhibited in broadly-defined “arts contexts” in a timely manner. Yesterday on the train to London, I drafted the conclusion of my dissertation. I left the overheated hostel I spent the night at to sweat through the overcrowded tube to South Kensington, and met Marie and Kristian to talk about the exhibition, and curating videogames more broadly in the museum cafe.

During our conversation, Marie thanked my boyfriend for a joke tweet he made re: a review which complained Grand Theft Auto was “missing” from the exhibition. I agreed that such an expectation is emblematic of the abortive, or maybe stillborn approach which defines most histories and attempts to exhibit videogames as a form. Despite the industry constantly emphasizing and directing our attention to the innovative and new, whenever a look back on this history of innovation is proposed, all but the latest console’s iteration of classic IP are at a risk of being inaccessible or unavailable. Major companies are far from universally reliable or consistent about maintaining the important documents of a videogame’s creation, or even the playability of the videogame itself, which already limits what you can display on top of negotiating temporary exhibition rights and how the game will be displayed and framed in the broader exhibition narrative. It limits the possibilities of the history that can be presented, period. Acquiring a videogame for longterm collection and conservation is also extremely rare.

Many exhibitions of videogames, especially those wanting to present a general historical overview which will offer an appealing and nostalgically validating selection of games to play, get mired down re-presenting what is already easily available and what major companies think is suitable to display. The result is a history about as living and complete as a dessicated bug pinned to a board, which is naturally what companies routinely cracking down on ROM sites (one of the only accessible ways to preserve many games) and fangames, and releasing walled garden retro consoles that only offer a tiny percentage of their actual library would want. And I mean, what would Grand Theft Auto even be doing in an exhibition which bills itself on focusing on emerging trends in videogames over the past decade-or-so? Sure, GTA V made a lot of money, but it’s hard to argue that it did this by being new or different, as Rockstar’s games have increasingly gone from edgy and experimental to simply following the genre rules they established, creating increasingly massive and overproduced open world containers that game reviewers have to masochistically slog through because it’s become expected, or rather inevitable that like 10 of these games have to come out a year. In many ways, this exhibition was intended for people who want something other than GTA.

Towards the end of our chat I admitted to Marie I hadn’t seen the exhibition yet. It makes me self conscious that my original plan was to not see the exhibition, deliberately, until it came to the new V&A in Dundee a few months after I will have submitted. I’m here anyways because I have to co-author a research paper with my PhD advisor to meet an outputs framework quota. He wants to examine the exhibition through the lens of “interfaces” as theorized by Alexander Galloway in The Interface Effect. The initial plan he proposed was for us to visit the exhibition together, very economically “making a day of it” with his 9 year old son as well. To this my primary response was dread but also:

Now I’m glad to do it alone, though, and move through at my own pace, alone with my thoughts. It is hard to maneuver around London as more than one person, I think after retreating from the V&A’s cafe to instead get lunch at a Pret 5 minutes away. (They did surgery on a grape voice) They charged £3.75 for a lemonade. I drink a £1.80 bottle of lemon and ginger juice (?) and eat some macaroni and cheese with kale mixed in out of a cardboard box instead, then gradually regroup, ensure I’ve gone to the restroom, that I’m comfortable, etc -- before showing my comped ticket and entering the exhibition.

The first section is divided by vertical walls of gray scrim, bringing to mind the off white monks cloth Alfred Barr originally covered the walls of the MoMA galleries in, but, due to their translucency, the scrims also create a hazy outline of what lay ahead, just outside of render distance. The area between each scrim has a quiet and cosy feeling, drawing attention to dense, medium-size displays which present the process underlying 8 videogames (of widely varying scales and types) from the past 10 years or so, giving them an intimate effect. Each takes a unique approach to what to highlight about each game. Journey’s area presents an enlarged spreadsheet document that was used to organize its narrative beats, as well as concept art (thankfully in lightboxes rather than on screens, a nice touch that just makes them easier to look at) and reference videos the team recorded, doing motion studies of fabric and sand atop some breezy sand dunes.

Bloodborne, on the other hand, while also presenting concept art and SketchUp models of the impressive cathedral areas in the game, primarily draws visitor attention towards the process of playing the game with a multi-screen display that combines a successful boss fight with a video of the player’s hands, a series of failed runs, and the player’s commentary. Kentucky Route Zero is defined mostly by its influences, from Magritte paintings to early New Media experiments, as is Consume Me, a work in progress by Jenny Jiao Hsia, which is accompanied by a selection of toys which contributed design ideas, as well as the storyboards and the artists’ laptop “at work,” displaying a screen capture video of Jenny using the Unity engine to build the game, as if she was invisibly controlling it. Some of these sections reveal more about the videogames’ creators by what they exclude, Nintendo’s Splatoon zone notably reticent presenting one short prototype video and a few polished sketches alongside completed work and merchandise, Tale of Tales’ artistic romanticism emphasizing the materiality of their notebooks as artefacts almost more than the content.

Mainstream videogames by major studios still seem a lot more controlling than smaller studios or independent creators, who may feel they have to be extra accomodating to show how glad they are to be featured (though in the case of Jenny Jiao Hsia and Cardboard Computer’s work, exposing a cutesy toy collection or tumblr inspo blog, while potentially embarrassing and personal to some people also deeply enriches the exhibition). Still, I was taken aback by certain elements of how Naughty Dog’s The Last of Us is displayed. The emphasis is on how motion capture, celebrity actors, and careful 3D set-making are combined to make a skillfully “cinematic” experience, but the elements presented, decontextualized and looping, Ellie dutifully performing her animations in rapid succession (duck, wave, crouch, pick up) on one screen, her actress dutifully T-posing irl before moving into position and delivering her lines in a grey full-body unitard, sort of makes the simulation fall apart instead. Higher resolution textures, better sound design, more polygons, more actors… all of these thing are (rather expensively) deployed to make games feel more cinematic and seamless but at their core, they are still repetitive clusters of modular parts, limited by computational logic. And humans end up giving the most ground, acting more like computers to make them and move through them.

The first section does most of the work the exhibition is trying to do to differentiate itself from the display style and official history increasingly canonized by many other videogame exhibitions, and the second area reinforces this by drawing attention to several issues which have shaped the criticism of mainstream videogames over the past decade. Sexism, racist representations and lack of representation are all mentioned, but the discussion of videogame violence was, unexpectedly, the most interesting to me. Given that the typical industry boosterism also likes to focus on hopeful developments for videogames as a form and industry becoming “accessible to all,” the discussions of racism and sexism, while welcome, were already familiar. (Also familiar was the breathless, precious tone of videogame site headlines selected to illustrate certain points. Do they really all sound this repetitive?) However, the industry and even sections of academia remain fixated on battling what feels like the satanic panic of the 1990s, insisting that videogame representations of violence have nothing to do with real violence, even as support from the military and arms manufacturers continues to have a major presence in game development, so it was surprising and refreshing to hear an interviewee say that videogames are usually structurally built around guns, even if they’re not shooters, because it’s the paradigm the technology has been created in.

This section includes Pippin Barr’s A Series of Shots In The Dark, which is, so far as I can tell, a one-button/button-agnostic game with a full keyboard, an interesting choice in a context where controllers other than the canonical 16-button console types are often simplified to corral visitors efficiently into correct interactions. The alternative key-based mice that are used to control Robert Yang’s Rinse and Repeat, however, are really frustrating to use, and I was belittled by nude hunks in front of a small crowd.

In the third area the ceiling dramatically opens up to a gigantic screen which shows a series of videos collaging various forms of fandom and fan production together. Minecraft is mediated by Minecraft youtubers (further mediated by the V&A steering their selections away from any foul language, or worse). 1000 permutations of the Overwatch character D-Va as reimagined by artists, cosplayers, custom PC builders… I was almost brought to tears by the scale of the screen itself for some reason, and a video of the underdog team named “Samsung Galaxy” winning the 2017 League of Legends championships very nearly put me over the edge. After exiting that room of the exhibition I checked the cycle tracking app on my phone and it informed me I was ovulating. I felt hormonal, tired, and slightly frazzled by how much I liked the exhibition so far, even if it is a bit corny to be so touched by a LoL montage. Despite a few small missteps (the video about the EVE Online community is mostly incoherent, expecting you to be able to root out tiny, significant bits of information from dense screens that mostly look like generic sci-fi scenes to the uninitiated) it was a surprise and weird, unexpected relief to not feel the same old frustration I had at other exhibitions.

The final section is by far the most arcade-like, maybe a concession to the overriding visitor expectations for the exhibition, aka, don’t I get to play something (fun)? But in the end it’s the area I felt distinctly let down by, and spent the least time in. It’s a good selection of videogames which reflect the increasing variety of approaches to indie/art/alt games, and they are mostly presented in impressive custom arcade cabinets covered with original artwork, with the exception of a few experimental alternative controller games which use hats with buttons on them, a fabric caterpillar, and half of a car (only the hat one was “playable,” for what it’s worth). Lingering among these familiar games I wished more attention was put towards the non-playable elements in the space. Posters for the events where these games were exhibited, important spaces for videogame developers to connect, support and share work at the margins of the videogame industry, and even though some were for events or places I had been, I didn’t feel like I got a good sense of what was specific to these locations. A Wild Rumpus party is, functionally, very different than the Babycastles gallery in New York, and each cultivates its own culture, but aside from a few photos or pieces of ephemera presented, these differences are mostly flattened, when they are some of the most interesting and important things about the contemporary videogames scene.

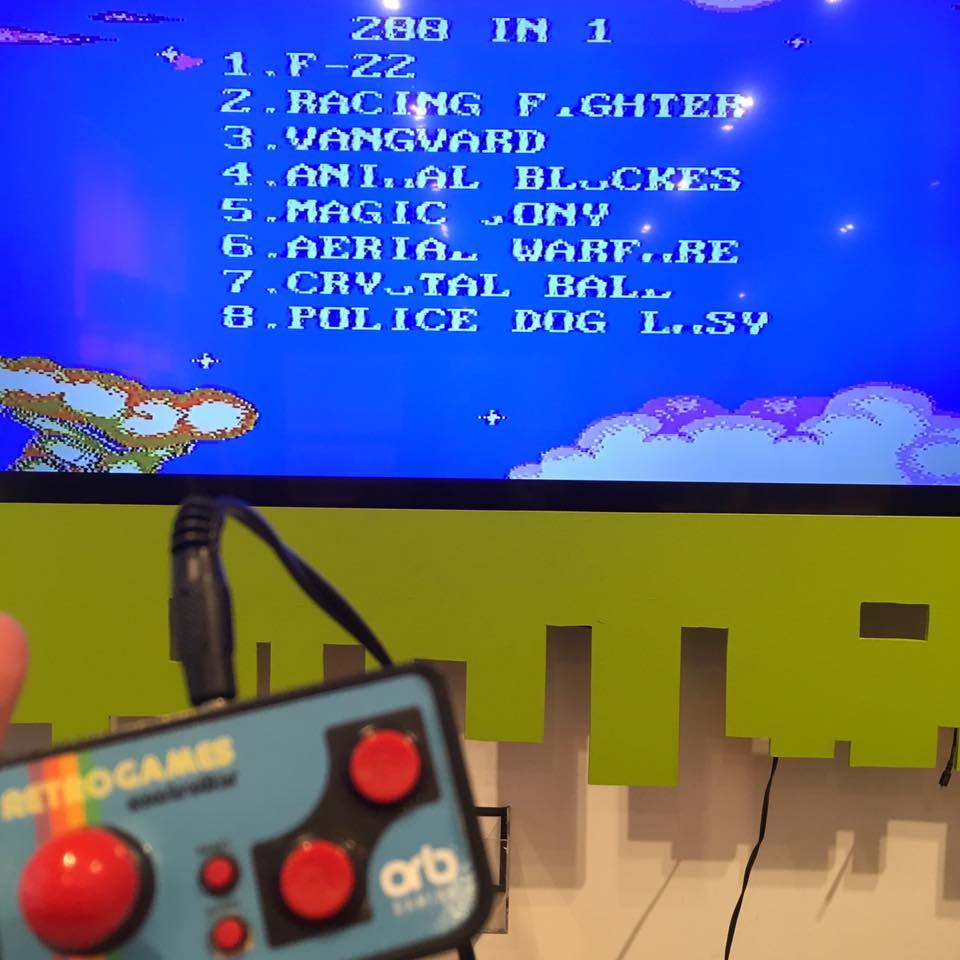

What is my review of VIDEO|GAMES? It does what I also hope my dissertation will do: it is a step towards a future where videogames are contemporary/living/art. How I picture this future? OK: As I left the exhibition, in the gift shop, there was a novelty 200-in-one shady off brand videogame device. It was weird to me that something like this was on sale here, in a venue which also sold what I’m sure is meticulously sourced and organic £3.75 lemonade, but I tried the demo unit that was plugged in to a large flat screen anyways. Through the disintegrating letters on its main menu I selected “CRYSTAL BALL.” The tiny device chugged to load a start screen, only 1P mode was available. I press start, and for a moment a pixelly ball with cartoon shoes renders slowly in a blocky labyrinth before the entire thing crashes; an ecstatic vision seen through a crack in which the mystery of videogames, shadowy international distribution networks, assets and code flipped and re-flipped, fragments coalescing into, if not a “whole,” a whole lot of something...

On the whole, videogames bore me, fairly conservative mainstream collections in one big noisy room even moreso, but there are also things about videogames that make them worthwhile, maybe: glimpses of their artifice, their brokenness, their strangeness that they even exist at all, which the V&A presents as a new way to look at them. (****)